Oscines: Passeri Linnaeus, 1766

Although the oscines and suboscines are readily identified, the proper classification of the oscines remained obscure for a long time. Sibley, Ahlquist, and Monroe took the first step of gathering the corvids together (albeit imperfectly). Their idea was that the oscines divided into two large groups, Corvida and Passerida. Their efforts were reflected in innovative checklists such as Gill's family list (1995) and the 3rd edition Howard-Moore checklist, both of which did a lot to group these birds in reasonable families. Contemporary checklists of a more traditional sort, such as Clements 5th edition list place the corvid assemblage all over the map.

Sibley and Ahlquist's view was that the remaining passerines split cleanly into a corvid group (Corvida) and a group containing everything else (Passerida). Further study has shown that reality is more complex. Unlike the Passerida, their version of the corvids was not a monophyletic group. Rather, their Corvida included a number of basal oscines as well as some basal Passerida. Nonetheless, further analysis has revealed a core group (Corvida) that is sister to the Passerida.

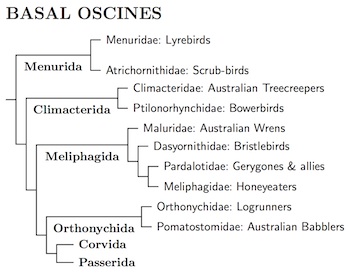

Basal Oscines

The Basal Oscines include ten families—Lyrebirds, Scrub-birds, Australasian Treecreepers, Bowerbirds, Australian Wrens, Bristlebirds, Pardalotes and Gerygones, Honeyeaters, Logrollers, and Australian Babblers arranged into four higher order groups which branch off separately before the split between the Corvida and Passerida (see Ericson et al., 2002a; Barker et al., 2004; Irestedt and Ohlson, 2008).

It is striking how the initial oscine radiation was confined to Australasia. We see this in the distribution of the basal oscines. All of the Menurida, Climacterida, and Pomatostomida are Australasian. Only Meliphagida has any species outside the area. Even there, two of the four families (Maluridae and Dasyornithidae) are also entirely Australasian. Further, only one of Pardalotidae crosses Wallace's line—the Golden-bellied Gerygone. That leaves the Meliphagidae, which have spread widely across Australasia and Oceania, with several species coming near Wallace's line. Even so, only one of them, the Indonesian Honeyeater, manages to ranges even barely into Indo-Malaya.

Jønsson et al. (2011b) offers some evidence concerning a possible relation between the emergence of the proto-Papuan archipelago and the oscine radiation. The New Scientist has a summary.

Menurida Sharpe, 1891

The first basal oscine branch, Menurida, is endemic to Australia. It consists of the lyrebirds (Menuridae) and scrub-birds (Atrichornithidae). Ericson et al. (2002b) found the Menurida sister to the rest of the oscines, but did not include scrub-birds in his analysis. Morphological analyses had placed the scrub-birds next to the lyrebirds. A genetic analysis by Chesser and ten Have (2007) concurs that the lyrebirds and scrub-birds are sister families, and also concurs with basic tree we present here. For a discussion of the history of lyrebird and scrub-bird taxonomy, see Ericson et al. (2002b) and Chesser and ten Have (2007), respectively.

Menuridae: Lyrebirds Lesson, 1828

1 genus, 2 species HBW-9

- Albert's Lyrebird, Menura alberti

- Superb Lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae

Atrichornithidae: Scrub-birds Stejneger, 1885 (1875)

1 genus, 2 species HBW-9

- Rufous Scrub-bird, Atrichornis rufescens

- Noisy Scrub-bird, Atrichornis clamosus

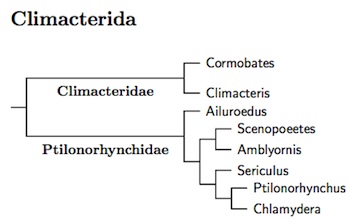

Climacterida Informal

The Climacterida, Meliphagida, and Orthonychida don't appear to have been formally named. They tend to be lumped together under terms such as “basal Corvida”. Nonetheless, it's been clear to many that there are 4-5 distinct clades here. I find it convenient for them to have names, so I've been using the first 3 since 2007, and started regarding the last as a parvorder in Feb. 2011.

The Climacterida are the next branch. There are two families here:

Australasian treecreepers (Climacteridae) and bowerbirds

(Ptilonorhynchidae). These families are endemic to Australasia.

The Climacterida are the next branch. There are two families here:

Australasian treecreepers (Climacteridae) and bowerbirds

(Ptilonorhynchidae). These families are endemic to Australasia.

The overall taxonomy is based on Ericson et al. (2002b) for Climactrida, and Christidis et al. (1996) and Kusmierski et al. (1997) for the bowerbirds.

Climacteridae: Australasian Treecreepers de Selys-Longchamps, 1839

2 genera, 7 species HBW-12

- White-throated Treecreeper, Cormobates leucophaea

- Papuan Treecreeper, Cormobates placens

- Red-browed Treecreeper, Climacteris erythrops

- White-browed Treecreeper, Climacteris affinis

- Rufous Treecreeper, Climacteris rufus

- Brown Treecreeper, Climacteris picumnus

- Black-tailed Treecreeper, Climacteris melanurus

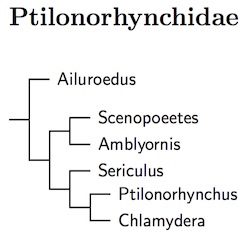

Ptilonorhynchidae: Bowerbirds G.R. Gray, 1841

6 genera, 27 species HBW-14

|

| Click for Ptilonorhynchidae species tree |

|---|

The overall organization of the Ptilonorhynchidae is based on Christidis et al. (1996) and Kusmierski et al. (1997). I've used two subfamilies, Ailuroedinae (catbirds) and Ptilonorhynchinae (bowerbirds) because Irestedt et al. (2016) indicates they have been separate for around 20 million years. There is some uncertainty about which branch of bowerbirds the Tooth-billed Bowerbird belongs to, or whether it is basal in the bowerbird subfamily (see Christidis et al., 1996 and Kusmierski et al., 1997). I am treating it as being sister to Amblyornis, as in Kusmierski et al. (1997).

I have accepted a number of splits in the Ailuroedus catbirds that were recommended by Irestedt et al. (2016) and adopted by IOC. They are:

- Split Tan-capped Catbird, Ailuroedus geislerorum (inc. molestus Rothschild & Hartert, 1929), and Ochre-breasted Catbird, Ailuroedus stonii (inc. cinnamomeus), from White-eared Catbird, Ailuroedus buccoides.

- Split Spotted Catbird, Ailuroedus melanotis into Spotted Catbird, Ailuroedus maculosus, Huon Catbird, Ailuroedus astigmaticus, Black-capped Catbird, Ailuroedus melanocephalus, Black-eared Catbird, Ailuroedus melanotis (inc. joanae and facialis) Arfak Catbird, Ailuroedus arfakianus (inc. misoliensis), and Northern Catbird, Ailuroedus jobiensis inc. guttaticollis.

Based on Zwiers et al. (2008), Sericulus ardens, has been split from Sericulus aureus. Interestingly, they are not each other's closest relatives. The name Flame Bowerbird follows S. ardens while S. aureus becomes Masked Bowerbird.

Ailuroedinae: Catbirds Iredale, 1948

- Ochre-breasted Catbird, Ailuroedus stonii

- White-eared Catbird, Ailuroedus buccoides

- Tan-capped Catbird, Ailuroedus geislerorum

- Green Catbird, Ailuroedus crassirostris

- Spotted Catbird, Ailuroedus maculosus

- Huon Catbird, Ailuroedus astigmaticus

- Black-capped Catbird, Ailuroedus melanocephalus

- Black-eared Catbird, Ailuroedus melanotis

- Arfak Catbird, Ailuroedus arfakianus

- Northern Catbird, Ailuroedus jobiensis

Ptilonorhynchinae: Bowerbirds G.R. Gray, 1841

- Tooth-billed Bowerbird, Scenopoeetes dentirostris

- Golden-fronted Bowerbird, Amblyornis flavifrons

- Streaked Bowerbird, Amblyornis subalaris

- Golden Bowerbird, Amblyornis newtoniana

- MacGregor's Bowerbird, Amblyornis macgregoriae

- Vogelkop Bowerbird, Amblyornis inornata

- Archbold's Bowerbird, Amblyornis papuensis

- Regent Bowerbird, Sericulus chrysocephalus

- Flame Bowerbird, Sericulus ardens

- Masked Bowerbird, Sericulus aureus

- Fire-maned Bowerbird, Sericulus bakeri

- Satin Bowerbird, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus

- Western Bowerbird, Chlamydera guttata

- Spotted Bowerbird, Chlamydera maculata

- Yellow-breasted Bowerbird, Chlamydera lauterbachi

- Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, Chlamydera cerviniventris

- Great Bowerbird, Chlamydera nuchalis

Meliphagida Informal

There are four families in the Meliphagida: Australasian wrens (Maluridae), bristlebirds (Dasyornithidae), gerygones and allies (Pardalotidae), and honeyeaters (Meliphagidae). We follow the order in Gardner et al. (2010). The Dasyornithidae have sometimes been included in Pardalotidae. However, the DNA shows that the Dasyornithidae are a separate branch of the Meliphagida.

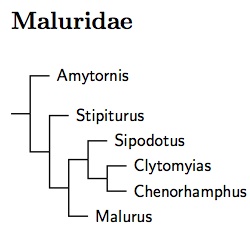

Maluridae: Australasian Wrens Swainson, 1831

5 genera, 32 species HBW-12

|

| Click for Maluridae tree |

|---|

The Maluridae are another family that is restricted to Australia and New Guinea. The arrangement here is based on Lee et al. (2012), Christidis et al. (2010) (Amytornis), and Driskell et al. (2011) (the other genera). Although these are not in 100% agreement, the differences are minor. When applicable, I've followed Lee et al. (2012), which uses considerably more data. Gardner et al. (2010) has sparser taxon sampling and includes only a little genetic data for these species. They give a slightly different tree.

Driskell et al. (2011) found that the broad-billed fairywrens were more closely related to Sipodotus and Clytomyias than to the rest of Malurus. They recommend putting them in a separate genus, Chenorhamphus (Oustalet 1878, type grayi), which I have done here.

Although Driskell et al. (2011) found that the Lovely Fairywren, M. amabilis is nested within the Variegated Fairywren, M. lamberti, a more detailed analysis by McLean et al. determined that they are sister species. This is consistent with reports that assimilis interbreeds with lamberti where they meet.

Based on Black et al. (2010) and Christidis et al. (2010), Thick-billed Grasswren, Amytornis textilis, is split into Western Grasswren, Amytornis textilis, and Thick-billed Grasswren, Amytornis modestus.

Based on Christidis et al. (2010, 2013), Pilbara Grasswren, Amytornis whitei, Sandhill Grasswren, Amytornis oweni, and Rusty Grasswren, Amytornis rowleyi, have been split from Striated Grasswren, Amytornis striatus.

- Gray Grasswren, Amytornis barbatus

- Short-tailed Grasswren, Amytornis merrotsyi

- White-throated Grasswren, Amytornis woodwardi

- Carpentarian Grasswren, Amytornis dorotheae

- Pilbara Grasswren, Amytornis whitei

- Sandhill Grasswren, Amytornis oweni

- Rusty Grasswren, Amytornis rowleyi

- Striated Grasswren, Amytornis striatus

- Western Grasswren, Amytornis textilis

- Thick-billed Grasswren, Amytornis modestus

- Black Grasswren, Amytornis housei

- Eyrean Grasswren, Amytornis goyderi

- Dusky Grasswren, Amytornis purnelli

- Kalkadoon Grasswren, Amytornis ballarae

- Southern Emuwren, Stipiturus malachurus

- Rufous-crowned Emuwren, Stipiturus ruficeps

- Mallee Emuwren, Stipiturus mallee

- Wallace's Fairywren, Sipodotus wallacii

- Orange-crowned Fairywren, Clytomyias insignis

- Broad-billed Fairywren, Chenorhamphus grayi

- Campbell's Fairywren, Chenorhamphus campbelli

- Emperor Fairywren, Malurus cyanocephalus

- Purple-crowned Fairywren, Malurus coronatus

- Variegated Fairywren, Malurus lamberti

- Lovely Fairywren, Malurus amabilis

- Blue-breasted Fairywren, Malurus pulcherrimus

- Red-winged Fairywren, Malurus elegans

- Splendid Fairywren, Malurus splendens

- Superb Fairywren, Malurus cyaneus

- White-winged Fairywren, Malurus leucopterus

- White-shouldered Fairywren, Malurus alboscapulatus

- Red-backed Fairywren, Malurus melanocephalus

Dasyornithidae: Bristlebirds Sibley & Ahlquist, 1985

1 genus, 3 species HBW-12

The bristlebirds are endemic to Australia.

- Eastern Bristlebird, Dasyornis brachypterus

- Western Bristlebird, Dasyornis longirostris

- Rufous Bristlebird, Dasyornis broadbenti

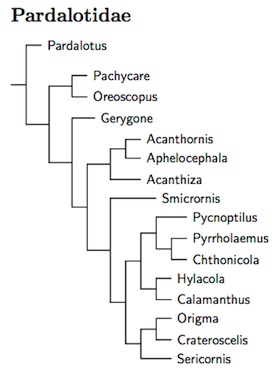

Pardalotidae: Gerygones and allies Strickland, 1842

16 genera, 69 species HBW-13

|

| Click for genus-level tree for Pardalotidae |

|---|

The Acanthizidae have been merged with the Pardalotidae. Although early genetic results had suggested that the pardalotes were more closely related to the honeyeaters than to the gerygones and thornbills, that seems to be incorrect. Relatively complete analyses, such as Gardner et al. (2010), Jønsson et al. (2011b), and Nyári (2011) have found that the pardalotes from a clade with the former Acanthizidae. Indeed, the pardalotes may even be nested inside!

Traditionally, the differences between these taxa have been considered relatively small, with all of them sometimes placed in a single family with the bristlebirds. We now know that the bristlebirds do not belong in this group, but that the remainer form a natural group of broadly similiar species. Such a group is best treated as a single family, and the name Pardalotidae has priority.

Although the Pardalotidae are primarily Australasian, with ranges east and south of Wallace's line, there is one exception—the Golden-bellied Gerygone. It ranges north to the Philippines and west to Malaysia and Sumatra.

The genus-level phylogenetic tree is mostly based on Gardner et al. (2010) and Nyári and Joseph (2012), with some help from Norman et al. (2009b), Nicholls et al. (2000), and Christidis et al. (1988). A number of species, especially those outside of Australia and New Guinea, still remain to be tested. They are marked with question marks on the tree.

Christidis and Boles (2008) was also consulted during the process. I've decided to use their generic limits, putting the heathwrens in Hylacola and the Speckled Warbler in Chthonicola.

Recent work by Norman et al. has led to some adjustment of the boundaries of Pardalotidae. Norman et al. (2009a) showed that the mohouas are not part of Pardalotidae, but rather belong in Corvoidea. In a second paper, Norman et al. (2009b) showed that the Goldenface, Pachycare flavogriseum, does belong in Pardalotidae, not Pachycephalidae, Petroicidae, or anyplace else that had previously been suggested.

- Red-browed Pardalote, Pardalotus rubricatus

- Striated Pardalote, Pardalotus striatus

- Spotted Pardalote, Pardalotus punctatus

- Forty-spotted Pardalote, Pardalotus quadragintus

- Goldenface, Pachycare flavogriseum

- Fernwren, Oreoscopus gutturalis

- Yellow-bellied Gerygone, Gerygone chrysogaster

- Brown Gerygone, Gerygone mouki

- Fairy Gerygone, Gerygone palpebrosa

- Green-backed Gerygone, Gerygone chloronota

- Plain Gerygone, Gerygone inornata

- White-throated Gerygone, Gerygone olivacea

- Golden-bellied Gerygone, Gerygone sulphurea

- Rufous-sided Gerygone, Gerygone dorsalis

- Large-billed Gerygone, Gerygone magnirostris

- Biak Gerygone, Gerygone hypoxantha

- Dusky Gerygone, Gerygone tenebrosa

- Fan-tailed Gerygone, Gerygone flavolateralis

- Brown-breasted Gerygone, Gerygone ruficollis

- Western Gerygone, Gerygone fusca

- Mangrove Gerygone, Gerygone levigaster

- Lord Howe Gerygone, Gerygone insularis

- Norfolk Gerygone, Gerygone modesta

- Gray Gerygone, Gerygone igata

- Chatham Gerygone, Gerygone albofrontata

- Scrubtit, Acanthornis magna

- Southern Whiteface, Aphelocephala leucopsis

- Chestnut-breasted Whiteface, Aphelocephala pectoralis

- Banded Whiteface, Aphelocephala nigricincta

- Striated Thornbill, Acanthiza lineata

- Yellow Thornbill, Acanthiza nana

- Gray Thornbill, Acanthiza cinerea

- New Guinea Thornbill, Acanthiza murina

- Yellow-rumped Thornbill, Acanthiza chrysorrhoa

- Inland Thornbill, Acanthiza apicalis

- Tasmanian Thornbill, Acanthiza ewingii

- Mountain Thornbill, Acanthiza katherina

- Brown Thornbill, Acanthiza pusilla

- Slender-billed Thornbill, Acanthiza iredalei

- Slaty-backed Thornbill, Acanthiza robustirostris

- Chestnut-rumped Thornbill, Acanthiza uropygialis

- Western Thornbill, Acanthiza inornata

- Buff-rumped Thornbill, Acanthiza reguloides

- Weebill, Smicrornis brevirostris

- Pilotbird, Pycnoptilus floccosus

- Redthroat, Pyrrholaemus brunneus

- Speckled Warbler, Chthonicola sagittatus

- Chestnut-rumped Heathwren, Hylacola pyrrhopygia

- Shy Heathwren, Hylacola cauta

- Striated Fieldwren, Calamanthus fuliginosus

- Western Fieldwren, Calamanthus montanellus

- Rufous Fieldwren, Calamanthus campestris

- Rockwarbler, Origma solitaria

- Rusty Mouse-warbler, Crateroscelis murina

- Bicolored Mouse-warbler, Crateroscelis nigrorufa

- Mountain Mouse-warbler, Crateroscelis robusta

- Yellow-throated Scrubwren, Sericornis citreogularis

- Pale-billed Scrubwren, Sericornis spilodera

- Papuan Scrubwren, Sericornis papuensis

- Gray-green Scrubwren, Sericornis arfakianus

- Buff-faced Scrubwren, Sericornis perspicillatus

- Vogelkop Scrubwren, Sericornis rufescens

- White-browed Scrubwren, Sericornis frontalis

- Atherton Scrubwren, Sericornis keri

- Tasmanian Scrubwren, Sericornis humilis

- Large Scrubwren, Sericornis nouhuysi

- Perplexing Scrubwren, Sericornis virgatus

- Tropical Scrubwren, Sericornis beccarii

- Large-billed Scrubwren, Sericornis magnirostra

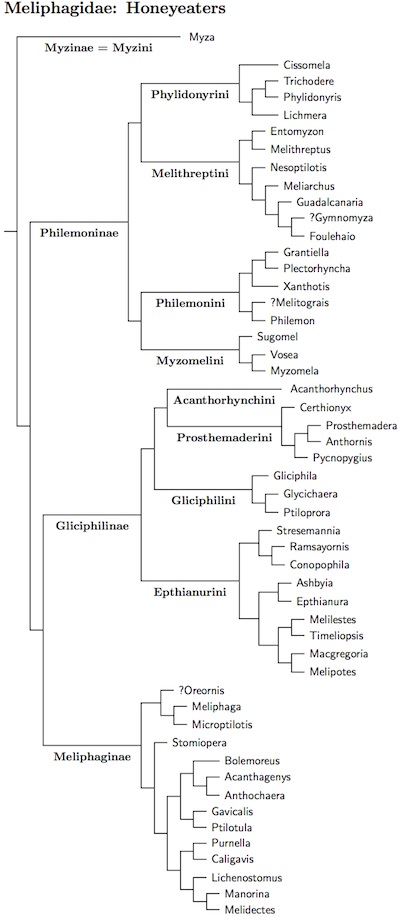

Meliphagidae: Honeyeaters Vigors, 1825

51 genera, 186 species HBW-13

Although they have spread widely. The Meliphagidae are primarily Australasian.

Some of them have colonized various islands in Oceania, and several have

spread into Wallacea, including the Lesser Sundas, Moluccas, and Sulawesi,

but only one occurs outside Australasia and Oceania. That is the

Indonesian Honeyeater. It barely crosses Wallace's line into Bali,

which is considered part of Indo-Malaya (aka the Oriental Region).

Although they have spread widely. The Meliphagidae are primarily Australasian.

Some of them have colonized various islands in Oceania, and several have

spread into Wallacea, including the Lesser Sundas, Moluccas, and Sulawesi,

but only one occurs outside Australasia and Oceania. That is the

Indonesian Honeyeater. It barely crosses Wallace's line into Bali,

which is considered part of Indo-Malaya (aka the Oriental Region).

The honeyeaters were substantially restructured by Sibley and Ahlquist (1990), losing the genera Cleptornis (Passerida), Oedistoma and Toxorhamphus (Melanocharitidae), and Promerops (Promeropidae), but gaining Epthianura and Ashbyia from the defunct Epthianuridae. Sibley and Ahlquist's addition of the Epthianura and Ashbyia to the honeyeaters has been supported by the more recent studies of Driskell and Christidis (2004) and Nyári and Joseph (2011).

Spring et al. (1995) found that the Bonin Honeyeater, Apalopteron familiare is not a honeyeater, but rather belongs in the Passerida (more precisely, Zosteropidae). More recently, Cracraft and Feinstein (2000) found that MacGregor's Bird-of-paradise, Macgregoria pulchra, is actually a honeyeater, while Ewen et al. (2006) and Driskell et al. (2007) found that the Stitchbird, Notiomystis cincta belongs near the Callaeidae, where it becomes a monotypic family. The now-extinct Hawaiian honeyeaters (genera Moho and Chaetoptila) were formerly considered to be part of this family, but they have recently been found to be related to waxwings (Fleischer et al., 2008).

Our understanding of honeyeater phylogeny is drawn from Driskell and Christidis (2004), Cracraft and Feinstein (2000), Norman et al. (2007), Higgins et al. (2008 = HBW-13), Gardner et al. (2010), Nyári and Joseph (2011), Andersen et al. (2014a), and Joseph et al. (2014a). There is enough information for a reasonable genus-level and even species-level taxonomy. There is some discrepancy at the higher levels, and I have doubts about how solid the overall ordering is. However, I've decided to follow the comprehensive study of Joseph et al. (2014a, Fig. 1) as it is based on a broader sampling of genes. There seem to be at least 10 major clades (treated as tribes) which I've arranged into 4 subfamilies.

Joseph et al. (2014a) were the only authors to consider Myza. They found that the two Myzas form a basal clade, here called Myzinae. The rest of the honeyeaters fell into 3 major clades, here ranked as subfamilies.

Philemoninae is next. In the phylogeny of Joseph et al. (2014a) it consists of 4 tribes: Phylidonyrini, Melithreptini, Philemonini, and Myzomelini.

Phylidonyrini contains another former member of Certhionyx, the Banded Honeyeater, Cissomela pectoralis, as well as Trichodere, Phylidonyris and Lichmera. Phylidonyrini is sister to Philemonini which contains the friarbirds and allied honeyeaters.

Melithreptini leads off with two species that have been moved from Lichenostomus and placed in genus Nesoptilotis (Mathews 1913, type flavicollis): White-eared Honeyeater, Nesoptilotis leucotis, and Yellow-throated Honeyeater, Nesoptilotis flavicollis. These are rather different from the rest of the former Lichenostomus, so it's not surprising that they end up in a different genus. I had originally made this change based on Higgins et al. (2008) and Gardner et al. (2010), before DNA data was available for both species. It is also supported by the complete analysis of Lichenostomus of Nyári and Joseph (2011).

Myzomelini primarly consists of Myzomela, with two monotypic genera: Sugomel and Vosea. Although Sugomel nigrum has often been placed in Certhionyx, Driskell and Christidis (2004) showed this was mistaken. Vosea is the Gilliard's Melidectes, which has been moved from Melidectes.

The next group in the Joseph et al. (2014a) phylogeny is Gliciphilinae. It also contains 4 tribes: Acanthorhynchini, Prosthemaderini, Gliciphilini, and Epthianurini.

The two spinebills lead off (Acanthorhynchini). They seem to be most closely related to Prosthemaderini, which contains several New Zealand endemics.

Note that Gliciphila has absorbed Glycifohia and that it belongs in Gliciphilini, sister to the Glycichaera/Ptiloprora clade (Andersen et al., 2014a).

Epthianurini contains the Australian Chats as well as various honeyeaters. In their study of MacGregor's “Bird-of-paradise”, Cracraft and Feinstein (2000) included representatives of four subfamilies. This was enough to show that Macgregoria is in the Epthianurinae. Joseph et al. (2014a) confirm it is sister to Melipotes.

The remainder of the Meliphagidae form the honeyeater clade Meliphaginae. Due to a deep genetic division found by Joseph et al. (2014a), all but three Meliphaga have been moved to Microptilotis (Mathews 1912, type gracilis), even though all but the three streaked species (albilineatus, fordianus and reticulatus) are very similar to the three Meliphaga.

In Meliphagine the big news is the restructuring of Lichenostomus. Gardner et al. (2010) had shown that Lichenostomus was polyphyletic, even after removing Nesoptilotis. Nyári and Joseph (2011) carried out a complete analysis of Lichenostomus using the mitochondrial ND2 and nuclear β-fibrinogen-7 genes. Their results were generally consistent with Gardner et al. (2010), but revealed some additional surprises that require further dismemberment of Lichenostomus and the use of three more genera: Bolemoreus, Caligavis, and Stomiopera. The Bridled Honeyeater (frenatus) and Eungella Honeyeater (hindwoodi) turn out to be sister to the wattlebirds plus Acanthagenys. Nyári and Joseph (2011) created the new genus Bolemoreus (type frenata) to accomodate them.

The other pieces of the former Lichenostomus run in a grade from Pitlotula to the miners (Manorina). The first clade is divided into two genera. Singing through Mangrove Honeyeaters take the name Gavicalis (Schodde and Mason 1999, type virescens) while for the Gray-fronted through Yellow-tinted Honeyeaters, the name Ptilotula (Mathews 1912, type flavescens) has priority Paraptilotis (Mathews 1912, type fuscus) because Ptilotula was chosen as a subgenus name by Schodde and Mason (1999) in preference to Paraptilotis. Then come the White-gaped and Yellow Honeyeaters, for which the name Stomiopera is available (Reichenbach 1852, type unicolor). This group is followed by three more former Lichenostomus honeyeater, now placed in Caligavis (Iredale 1956, type obscura). The Lichenostomus grade is interrupted by Purnella albifrons, sometimes placed in Phylidonyris. Then we finally reach the remaining Lichenostomus, now reduced to two species.

Based on Toon et al. (2010), Gilbert's Honeyeater, Melithreptus chloropsis has been split from White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus. They also found evidence that the White-throated Honeyeater, Melithreptus albogularis, may contain more than one species, but more study is necessary to clarify the situation.

Based on Andersen et al. (2014), Giant Honeyeater, Foulehaio viridis, has been split into Yellow-billed Honeyeater, Gymnomyza viridis, and Giant Honeyeater, Gymnomyza brunneirostris.

Following IOC 5.2, the English names of three Foulehaio honeyeaters have been changed:

- Viti Levu Honeyeater, Foulehaio procerior, becomes Kikau

- Vanua Levu Honeyeater, Foulehaio taviunensis, becomes Lesser Wattled-Honeyeater

- Polynesian Honeyeater, Foulehaio carunculatus, becomes Polynesian Wattled-Honeyeater

Myzinae: Myzas Informal

- Dark-eared Myza, Myza celebensis

- White-eared Myza, Myza sarasinorum

Philemoninae: Friarbirds & allies Lesson, 1828

Phylidonyrini Matthews, 1946

- Banded Honeyeater, Cissomela pectoralis

- White-streaked Honeyeater, Trichodere cockerelli

- Crescent Honeyeater, Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus

- White-cheeked Honeyeater, Phylidonyris niger

- New Holland Honeyeater, Phylidonyris novaehollandiae

- Scaly-crowned Honeyeater, Lichmera lombokia

- Olive Honeyeater, Lichmera argentauris

- Indonesian Honeyeater, Lichmera limbata

- Brown Honeyeater, Lichmera indistincta

- Gray-eared Honeyeater, Lichmera incana

- Silver-eared Honeyeater, Lichmera alboauricularis

- Scaly-breasted Honeyeater, Lichmera squamata

- Buru Honeyeater, Lichmera deningeri

- Seram Honeyeater, Lichmera monticola

- Flame-eared Honeyeater, Lichmera flavicans

- Black-necklaced Honeyeater, Lichmera notabilis

Melithreptini G.R. Gray, 1841

- Blue-faced Honeyeater, Entomyzon cyanotis

- Gilbert's Honeyeater, Melithreptus chloropsis

- White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus

- Black-headed Honeyeater, Melithreptus affinis

- White-throated Honeyeater, Melithreptus albogularis

- Strong-billed Honeyeater, Melithreptus validirostris

- Black-chinned Honeyeater, Melithreptus gularis

- Brown-headed Honeyeater, Melithreptus brevirostris

- White-eared Honeyeater, Nesoptilotis leucotis

- Yellow-throated Honeyeater, Nesoptilotis flavicollis

- Makira Honeyeater, Meliarchus sclateri

- Guadalcanal Honeyeater, Guadalcanaria inexpectata

- Crow Honeyeater, Gymnomyza aubryana

- Giant Honeyeater, Foulehaio brunneirostris

- Yellow-billed Honeyeater, Foulehaio viridis

- Kadavu Honeyeater, Foulehaio provocator

- Mao, Foulehaio samoensis

- Kikau Honeyeater, Foulehaio procerior

- Lesser Wattled-Honeyeater, Foulehaio taviunensis

- Polynesian Wattled-Honeyeater, Foulehaio carunculatus

Philemonini: Friarbirds & allies Lesson, 1828

- Painted Honeyeater, Grantiella picta

- Striped Honeyeater, Plectorhyncha lanceolata

- Spotted Honeyeater, Xanthotis polygrammus

- Macleay's Honeyeater, Xanthotis macleayanus

- Tawny-breasted Honeyeater, Xanthotis flaviventer

- White-streaked Friarbird, Melitograis gilolensis

- Meyer's Friarbird, Philemon meyeri

- Brass's Friarbird, Philemon brassi

- Little Friarbird, Philemon citreogularis

- Gray Friarbird, Philemon kisserensis

- Timor Friarbird, Philemon inornatus

- Dusky Friarbird, Philemon fuscicapillus

- Seram Friarbird, Philemon subcorniculatus

- Black-faced Friarbird, Philemon moluccensis

- Tanimbar Friarbird, Philemon plumigenis

- Helmeted Friarbird, Philemon buceroides

- New Guinea Friarbird, Philemon novaeguineae

- New Britain Friarbird, Philemon cockerelli

- New Ireland Friarbird, Philemon eichhorni

- Manus Friarbird, Philemon albitorques

- Silver-crowned Friarbird, Philemon argenticeps

- Noisy Friarbird, Philemon corniculatus

- New Caledonian Friarbird, Philemon diemenensis

Myzomelini: Myzomela & allies G.R. Gray, 1840

- Black Honeyeater, Sugomel nigrum

- Gilliard's Melidectes, Vosea whitemanensis

- Drab Myzomela, Myzomela blasii

- White-chinned Myzomela, Myzomela albigula

- Ashy Myzomela, Myzomela cineracea

- Ruby-throated Myzomela, Myzomela eques

- Dusky Myzomela, Myzomela obscura

- Red Myzomela, Myzomela cruentata

- Papuan Black Myzomela, Myzomela nigrita

- New Ireland Myzomela, Myzomela pulchella

- Crimson-hooded Myzomela, Myzomela kuehni

- Red-headed Myzomela, Myzomela erythrocephala

- Sumba Myzomela, Myzomela dammermani

- Mountain Myzomela, Myzomela adolphinae

- Rotuma Myzomela, Myzomela chermesina

- Sulawesi Myzomela, Myzomela chloroptera

- Wakolo Myzomela, Myzomela wakoloensis

- Banda Myzomela, Myzomela boiei

- Scarlet Myzomela, Myzomela sanguinolenta

- New Caledonian Myzomela, Myzomela caledonica

- Cardinal Myzomela, Myzomela cardinalis

- Micronesian Myzomela, Myzomela rubratra

- Sclater's Myzomela, Myzomela sclateri

- Bismarck Black Myzomela, Myzomela pammelaena

- Red-capped Myzomela, Myzomela lafargei

- Crimson-rumped Myzomela, Myzomela eichhorni

- Red-vested Myzomela, Myzomela malaitae

- Black-headed Myzomela, Myzomela melanocephala

- Sooty Myzomela, Myzomela tristrami

- Sulphur-breasted Myzomela, Myzomela jugularis

- Black-bellied Myzomela, Myzomela erythromelas

- Black-breasted Myzomela, Myzomela vulnerata

- Red-collared Myzomela, Myzomela rosenbergii

Gliciphilinae Reichenbach, 1882

Acanthorhynchini: Spinebills Mathews, 1946

- Western Spinebill, Acanthorhynchus superciliosus

- Eastern Spinebill, Acanthorhynchus tenuirostris

Prosthemaderini Informal

- Pied Honeyeater, Certhionyx variegatus

- Tui / Parson Bird, Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae

- New Zealand Bellbird, Anthornis melanura

- Chatham Bellbird, Anthornis melanocephala

- Plain Honeyeater, Pycnopygius ixoides

- Marbled Honeyeater, Pycnopygius cinereus

- Streak-headed Honeyeater, Pycnopygius stictocephalus

Gliciphilini Reichenbach, 1882

- Barred Honeyeater, Gliciphila undulata

- Tawny-crowned Honeyeater, Gliciphila melanops

- White-bellied Honeyeater, Gliciphila notabilis

- Green-backed Honeyeater, Glycichaera fallax

- Leaden Honeyeater, Ptiloprora plumbea

- Yellowish-streaked Honeyeater, Ptiloprora meekiana

- Rufous-sided Honeyeater, Ptiloprora erythropleura

- Rufous-backed Honeyeater, Ptiloprora guisei

- Mayr's Honeyeater, Ptiloprora mayri

- Gray-streaked Honeyeater, Ptiloprora perstriata

Epthianurini: Australian Chats & allies Legge, 1887

- Bougainville Honeyeater, Stresemannia bougainvillei

- Bar-breasted Honeyeater, Ramsayornis fasciatus

- Brown-backed Honeyeater, Ramsayornis modestus

- Rufous-banded Honeyeater, Conopophila albogularis

- Rufous-throated Honeyeater, Conopophila rufogularis

- Gray Honeyeater, Conopophila whitei

- Gibberbird, Ashbyia lovensis

- Yellow Chat, Epthianura crocea

- Crimson Chat, Epthianura tricolor

- White-fronted Chat, Epthianura albifrons

- Orange Chat, Epthianura aurifrons

- Long-billed Honeyeater, Melilestes megarhynchus

- Tawny Straightbill, Timeliopsis griseigula

- Olive Straightbill, Timeliopsis fulvigula

- MacGregor's Honeyeater, Macgregoria pulchra

- Arfak Honeyeater, Melipotes gymnops

- Common Smoky-Honeyeater, Melipotes fumigatus

- Wattled Smoky-Honeyeater, Melipotes carolae

- Spangled Honeyeater, Melipotes ater

Meliphaginae: Honeyeaters, Wattlebirds, Miners Vigors, 1825

Meliphagini: Honeyeaters, Wattlebirds, Miners Vigors, 1825

- Orange-cheeked Honeyeater, Oreornis chrysogenys

- Puff-backed Honeyeater, Meliphaga aruensis

- Yellow-spotted Honeyeater, Meliphaga notata

- Lewin's Honeyeater, Meliphaga lewinii

- Scrub Honeyeater, Microptilotis albonotatus

- Mountain Honeyeater, Microptilotis orientalis

- Mimic Honeyeater, Microptilotis analogus

- Forest Honeyeater, Microptilotis montanus

- Mottle-breasted Honeyeater, Microptilotis mimikae

- Elegant Honeyeater, Microptilotis cinereifrons

- Graceful Honeyeater, Microptilotis gracilis

- Tagula Honeyeater, Microptilotis vicinus

- Yellow-gaped Honeyeater, Microptilotis flavirictus

- Streak-breasted Honeyeater, Microptilotis reticulatus

- Kimberley Honeyeater, Microptilotis fordiana

- White-lined Honeyeater, Microptilotis albilineatus

- White-gaped Honeyeater, Stomiopera unicolor

- Yellow Honeyeater, Stomiopera flava

- Bridled Honeyeater, Bolemoreus frenatus

- Eungella Honeyeater, Bolemoreus hindwoodi

- Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater, Acanthagenys rufogularis

- Western Wattlebird, Anthochaera lunulata

- Little Wattlebird, Anthochaera chrysoptera

- Regent Honeyeater, Anthochaera phrygia

- Red Wattlebird, Anthochaera carunculata

- Yellow Wattlebird, Anthochaera paradoxa

- Varied Honeyeater, Gavicalis versicolor

- Singing Honeyeater, Gavicalis virescens

- Mangrove Honeyeater, Gavicalis fasciogularis

- White-plumed Honeyeater, Ptilotula penicillata

- Yellow-plumed Honeyeater, Ptilotula ornata

- Yellow-tinted Honeyeater, Ptilotula flavescens

- Fuscous Honeyeater, Ptilotula fusca

- Gray-headed Honeyeater, Ptilotula keartlandi

- Gray-fronted Honeyeater, Ptilotula plumula

- White-fronted Honeyeater, Purnella albifrons

- Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Caligavis chrysops

- Obscure Honeyeater, Caligavis obscura

- Black-throated Honeyeater, Caligavis subfrenata

- Purple-gaped Honeyeater, Lichenostomus cratitius

- Yellow-tufted Honeyeater, Lichenostomus melanops

- Bell Miner, Manorina melanophrys

- Noisy Miner, Manorina melanocephala

- Black-eared Miner, Manorina melanotis

- Yellow-throated Miner, Manorina flavigula

- Sooty Melidectes, Melidectes fuscus

- Short-bearded Melidectes, Melidectes nouhuysi

- Long-bearded Melidectes, Melidectes princeps

- Cinnamon-browed Melidectes, Melidectes ochromelas

- Vogelkop Melidectes, Melidectes leucostephes

- Belford's Melidectes, Melidectes belfordi

- Yellow-browed Melidectes, Melidectes rufocrissalis

- Huon Melidectes, Melidectes foersteri

- Ornate Melidectes, Melidectes torquatus

Orthonychida Informal

The last two basal oscine families are the logrunners (Orthonychidae) and Australasian babblers (Pomatostomidae). The massive multigene analysis of Aggerbeck et al. (2014) finds them to be sisters, albeit fairly deeply separated. They split off before the division between the Corvida and Passerida, which means they are in the basal oscines.

Orthonychidae: Logrunners G.R. Gray, 1840

1 genus, 3 species HBW-12

The logrunners are found in Australia and New Guinea.

- Papuan Logrunner, Orthonyx novaeguineae

- Australian Logrunner, Orthonyx temminckii

- Chowchilla, Orthonyx spaldingii

Pomatostomidae: Australasian Babblers Schodde, 1975

2 genera, 5 species HBW-12

As befits their name, the Australasian babblers are found in Australia and New Guinea.

- Papuan Babbler, Garritornis isidorei

- Gray-crowned Babbler, Pomatostomus temporalis

- Hall's Babbler, Pomatostomus halli

- White-browed Babbler, Pomatostomus superciliosus

- Chestnut-crowned Babbler, Pomatostomus ruficeps