PASSERIFORMES Linnaeus, 1766

The name Passeriformes (in the form Passeres) has been attributed to Linnaeus, 1766. In the absence of a code for order-level names, I rather reluctantly continue that because other choices may create nomenclatural havoc. However, it suffers from a problem. Linnaeus did not base it on a genus name he used. Indeed, he already used in in 1758. In 1766, he at least mentions the genus Passer, citing Brisson. However, he considered the House Sparrow to be Fringilla domestica, not Passer domesticus. Thus Passeres is not properly based on a genus name. According to Brodkorb (1978), who does attribute Passeriformes to Linnaeus, Nitzsch, 1820 is next in the priority line, but I have similar doubts about his use of Passer also. I think strictly enforcing the requirement that the order-level name be based on one of the genera used in the text would end up giving priority to Corviformes or Hirundiformes (Wagler, 1830).

There are not only more passerines than any other order of birds, there more passerines than all of the other orders put together. Nearly 60% of all extant bird species are Passeriformes.

Although we have long known which birds are passerines and which are not, their relationships have been poorly understood. A comparison of Clements 5th edition (which uses an old taxonomy) and Howard-Moore 3rd and 4th editions shows how much revision has been necessary. Many passerines have been classified in the wrong family (and genus) which made it harder to determine proper family boundaries and relations. Recent work on passerine taxonomy has done much to clarify the situation, although some issues still remain.

Jarvis et al. (2014) estimate that the Passeriformes-Psittaciformes split occurred approximately 55 mya, but that the basal split within Passeriforems (between Acanthisitti and the rest) dates to only 39 mya. So what happened during those first 16 million years? The fossil record sheds some light on this. The earliest fossils that may belong to the Passeriform crown group date from the Oligocene, but there are some Eocene fragments that may be stem group Passeriforems (see Mayr 2009 for more). However, there is a extinct sister group to the Passeriformes, the Zygodactylidae (Mayr, 2008b; Mayr, 2011; DeBee, 2012). Fossils of the Zygodactylidae have been found starting in the early Eocene (Green River Formation, Wyoming; sDanish Fur Formation, Denmark) to the middle Miocene (France, ca. 12 mya). Based on the fossil evidence, these were once one of the most abundant small birds (Mayr, 2009).

Unlike modern Passeriformes, Zygodactylidae have a zygodactyl foot. This may indicate their common heritage with the zygodactyl parrots. Boletho et al. (2014), in a study of foot development, indicate how this may have occurred.

New Zealand Wrens: Acanthisitti Wolters, 1977

Until recently the New Zealand wrens were considered suboscines. However, the passerines have a basal split between the New Zealand wrens and all other songbirds (Barker et al., 2002; Barker et al., 2004). The common ancestor of the suboscines and the oscine passerines comes after the split between the New Zealand wrens, so we cannot put the New Zealand wrens in the suboscines. That not only forces them into their own family, but into their own suborder, Acanthisitti.

The Acanthisittidae are endemic to New Zealand. Together with the oldest splits among the suboscines and oscines, this suggest a southern origin for the Passeriform crown group. Attempts to date the split between the Acanthisittidae and the other passerines using vicariance suggest that it may date to the period when New Zealand separated from a still-joined Australia and Antarctica (see Ericson et al., 2002a). However, Jarvis et al. (2014) date the split much later, around 2014.

Acanthisittidae: New Zealand Wrens Sundevall, 1872

2 genera, 4 species HBW-9

- Rifleman, Acanthisitta chloris

- Bushwren, Xenicus longipes

- New Zealand Rockwren, Xenicus gilviventris

- Stephens Island Wren, Xenicus lyalli

EUPASSERES Ericson et al., 2002b

The remaining passeriformes are called the Eupasseres. They consist of the oscines (Passeri) and the suboscines (Tyranni).

Suboscines: Tyranni Wetmore & Miller, 1926

The oscines have roots in Australia. The origin of the suboscines (Tyranni) is less clear. One group, the ancestral Tyrannides, went to the Americas (probably South America), while the ancestral Eurylaimides went to the Old World (India?). Although South America and India were once joined with Australia-Antarctica as Gondwana, the separation between them seems to long predate the split between the oscines and suboscines.

One possibility is that all originated when Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica were still joined, with the ancestral Acanthisittidae in the portion that became New Zealand, the ancestral oscines in the Australian part, and the suboscines in the Antarctic part (which may have had a subtropical climate then). The western suboscines (ancestral Tyrannides) could have easily made their way to South America. The Eurylaimides remain a problem. One suggestion is that the eastern suboscines spread onto the now-submerged Kerguelen Plateau, and thence to India (see Moyle et al., 2006a). They could then ride along as India drifted into Asia.

My current view is that these naive vicariance ideas are just wrong, and that the suboscines got where they are by flying.

The oscine group is bigger, so we consider it the main trunk, and investigate the smaller suboscine branch first. It has two parts, the Old World Eurylaimides and the New World Tyrannides.

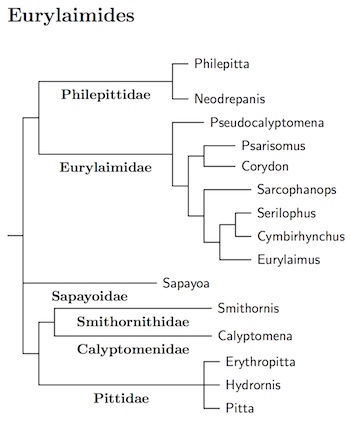

Old World Suboscines: Eurylaimides Seebohm, 1890

Like the passerines as a whole, the suboscines have generally been

identifiable as suboscine, but teasing out the relationships between the

suboscines has been difficult. The next division is between the Old

World subsocines plus Sapayoa (Eurylaimides) and the New World suboscines (Tyrannides).

The general arrangement of the Old World suboscines, the pittas, asities, and

broadbills, and Sapayoa now follows Prum et al. (2015). They did not include the

Sapayoa in their analysis.

Like the passerines as a whole, the suboscines have generally been

identifiable as suboscine, but teasing out the relationships between the

suboscines has been difficult. The next division is between the Old

World subsocines plus Sapayoa (Eurylaimides) and the New World suboscines (Tyrannides).

The general arrangement of the Old World suboscines, the pittas, asities, and

broadbills, and Sapayoa now follows Prum et al. (2015). They did not include the

Sapayoa in their analysis.

The Sapayoa, Sapayoa aenigma, has found a new home in this group as the only New World representative of the Eurylaimides (see Fjeldså et al., 2003; Chesser, 2004). However, where exactly it fits in remains unresolved. I know of four papers that include Sapayoa— Fjeldså et al., 2003; Chesser, 2004; Irestedt et al. (2006b); Moyle et al., (2006a). Between them, they've analyzed 9 different genes. Unfortunately, there's no consensus on where Sapayoa goes. It belongs somewhere in Eurylaimides. It could be basal, could be sister to Pittidae, or to Calyptomenidae plus Smithornithidae, or to Philepittidae plus Eurylaimidae.

Moyle et al. (2006a) found that the broadbills were not a natural grouping. Some are more closely related to the asities (and perhaps Sapayoa) than they are to the other broadbills. This list considers the broadbills to consist of three families, one of them sister to the asities, the other two are sister to each other, and then to the Pittidae. The list starts with the asities.

Philepittidae: Asities Sharpe, 1870

2 genera, 4 species HBW-8

The Asities of Madagascar are also placed in their own family. Prum et al. (2015) found that the division between the Philepittidae and Eurylaimidae dates to about 20 mya, in the early Miocene.

- Velvet Asity, Philepitta castanea

- Schlegel's Asity, Philepitta schlegeli

- Common Sunbird-Asity, Neodrepanis coruscans

- Yellow-bellied Sunbird-Asity, Neodrepanis hypoxantha

Eurylaimidae: Eurylaimid Broadbills Lesson, 1831

7 genera, 9 species HBW-8

Except for Grauer's Broadbill, this family is Indo-Malayan.

- Grauer's Broadbill, Pseudocalyptomena graueri

- Long-tailed Broadbill, Psarisomus dalhousiae

- Dusky Broadbill, Corydon sumatranus

- Wattled Broadbill, Sarcophanops steerii

- Visayan Broadbill, Sarcophanops samarensis

- Silver-breasted Broadbill, Serilophus lunatus

- Black-and-red Broadbill, Cymbirhynchus macrorhynchos

- Banded Broadbill, Eurylaimus javanicus

- Black-and-yellow Broadbill, Eurylaimus ochromalus

Sapayoidae: Sapayoa Irestedt et al., 2006

1 genus, 1 species Not HBW Family (HBW-9:167)

The Sapayoa is on its own old branch in Eurylaimides. It is the Old World Suboscine in the Neotropics. There were likely many more members of its clade, with it the only survivor.

- Sapayoa, Sapayoa aenigma

Smithornithidae: African Broadbills Bonaparte, 1853

1 genus, 3 species Not HBW Family (HBW-8:83-4)

The division between African Smithornis and Calyptomena of Sundaland is quite deep. Prum et al. (2015) estimate put it in the early-Miocene, approximately 20 million years ago. It seems reasonable to put them in separate families.

- African Broadbill, Smithornis capensis

- Gray-headed Broadbill, Smithornis sharpei

- Rufous-sided Broadbill, Smithornis rufolateralis

Calyptomenidae: Asian Green Broadbills Bonaparte, 1850

1 genus, 3 species Not HBW Family (HBW-8:84-5)

- Green Broadbill, Calyptomena viridis

- Hose's Broadbill, Calyptomena hosii

- Whitehead's Broadbill, Calyptomena whiteheadi

Pittidae: Pittas Swainson, 1831

3 genera, 34 species HBW-8

Pitta taxonomy follows Irestedt et al., (2006b), who recommended resurrecting the genera Erythropitta and Hydrornis.

The Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta erythrogaster, has been split into Northern Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta erythrogaster, and Southern Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta macklotii. The Southern Red-bellied Pitta consists of birds from the Moluccas, New Guinea and Australia. The Northern Red-bellied Pitta ranges over the Philippines and the Indonesia except for the Moluccas. See Irestedt et al. (2013).

Based on Rheindt and Eaton (2010), the Banded Pitta, Hydrornis guajanus is split into three species: Malayan Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis irena, Bornean Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis schwaneri, and Javan Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis guajanus. Since these are allopatric taxa, it is difficult to establish appropriate species limits. In my mind, the fact that irena seems to cross water barriers that are comparable to those separating the other two species suggests that more than water separates them, that they are biological species.

Sula Pitta, Erythropitta dohertyi, is now treated as a subspecies of Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta erythrogaster, because of a lack of vocal differences (Rheindt et al., 2010).

- Whiskered Pitta, Erythropitta kochi

- Northern Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta erythrogaster

- Southern Red-bellied Pitta, Erythropitta macklotii

- Blue-banded Pitta, Erythropitta arquata

- Garnet Pitta, Erythropitta granatina

- Black-crowned Pitta, Erythropitta ussheri

- Graceful Pitta, Erythropitta venusta

- Eared Pitta, Hydrornis phayrei

- Rusty-naped Pitta, Hydrornis oatesi

- Blue-naped Pitta, Hydrornis nipalensis

- Blue-rumped Pitta, Hydrornis soror

- Giant Pitta, Hydrornis caeruleus

- Schneider's Pitta, Hydrornis schneideri

- Blue Pitta, Hydrornis cyaneus

- Bar-bellied Pitta, Hydrornis elliotii

- Gurney's Pitta, Hydrornis gurneyi

- Blue-headed Pitta, Hydrornis baudii

- Malayan Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis irena

- Bornean Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis schwaneri

- Javan Banded-Pitta, Hydrornis guajanus

- African Pitta, Pitta angolensis

- Green-breasted Pitta, Pitta reichenowi

- Indian Pitta, Pitta brachyura

- Mangrove Pitta, Pitta megarhyncha

- Blue-winged Pitta, Pitta moluccensis

- Hooded Pitta, Pitta sordida

- Fairy Pitta, Pitta nympha

- Azure-breasted Pitta, Pitta steerii

- Noisy Pitta, Pitta versicolor

- Ivory-breasted Pitta, Pitta maxima

- Elegant Pitta, Pitta elegans

- Black-faced Pitta, Pitta anerythra

- Superb Pitta, Pitta superba

- Rainbow Pitta, Pitta iris