ARDEAE Wagler, 1830

Although the Jarvis et al. (2014) tree suggests that the Eurypgimorphae belong with the Aequornithes, support for this is a little soft. For that reason I have put them in separate superorders.

EURYPYGIMORPHAE Fürbringer, 1888

Traditional classifications of the tropicbirds have usually focused on the totipalmate feet and grouped them with the traditional Pelecaniformes. The Pelicaniformes also have totipalmate feet: frigatebirds, boobies, anhingas, cormorants, and pelicans. The tropicbirds have long been recognized as being somewhat different. More recently, the pelicans and fregatebirds have also been considered a bit different. Morphological analyses continued to show this even in the phylogenetic era. Cracraft (1985) considered the tropicbirds different enough that he divided the Pelicaniformes into two suborders: Phaethontes (tropicbirds) and Steganopodes (the rest). He further separated the frigatebirds as a infraorder and pelicans as a superfamily, leaving the boobies, cormorants, and anhingas more closely grouped. There is a lot of truth to this sort of arrangement.

However, what it misses is that the totipalmate birds are not a natural group! Hedges and Sibley (1994) used DNA hybridization to argue that not only did the pelicans and frigatebirds not belong with the group, but that the tropicbird also didn't belong.

In fact, their Figure 2 is quite interesting. If you try to map it onto the tree I'm using, you find that the tropicbirds are outside the Aequornithes entirely. More recent DNA analyses based on sequences usually put the frigatebirds (but not pelicans) in a group with the boobies, gannets, cormorants, and darters. We follow that here.

More recent genetic studies, such as that of van Tuinen et al. (2001) have more decisively broken up the totipalmate group. In particular van Tuinen et al. correctly placed the pelicans close to the Hamerkop and Shoebill. The various studies supporting Metaves, including Fain and Houde (2004), Ericson et al. (2006a), and Hackett et al. (2008), all included the tropicbirds in Metaves, well separated from the rest of the totipalmate birds. They also all supported a close relationship between the Hamerkop, Shoebill, and pelicans.

Nonetheless, there were still problems with the tropicbirds. Using complete mitochondrial genomes, Gibb et al. (2013) found the tropicbirds nowhere near the rest of the “Pelicaniformes”. McCormack et al. (2013) placed the topicbirds near the Kagu in a grouping reminiscent of Metaves (but different). Finally, the data-intensive analysis by Jarvis et al. (2014) found that Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes were sister orders, with 100% bootstrap support. Moreover, they placed the Kagu/Sunbittern/tropicbird group sister to Aequornithes, as is done here.

The arrangement in Jarvis et al. (2014) suggests that totipalmate feet developed at least three times: in the tropicbirds, pelicans, and Suliformes.

EURYPYGIFORMES Fürbringer, 1888

These two monotypic families form a strongly supported clade in Hackett et al. (2008). Their affinities have long been unclear. They had recently been grouped near the cranes, but that appears incorrect. Ericson et al. (2006a) put them in Metaves near Columbea while Hackett et al. (2008) had them sister to the Strisores (also in Metaves). However, Jarvis et al. (2014) have them sister to the tropicbirds and near the waterbird group, Aequornithes.

Rhynochetidae: Kagu Carus, 1868

1 genus, 1 species HBW-3

- Kagu, Rhynochetos jubatus

Eurypygidae: Sunbittern Selby, 1840

1 genus, 1 species HBW-3

- Sunbittern, Eurypyga helias

PHAETHONTIFORMES Sharpe, 1891

Phaethontidae: Tropicbirds Brandt, 1840

1 genus, 3 species HBW-1

- Red-billed Tropicbird, Phaethon aethereus

- Red-tailed Tropicbird, Phaethon rubricauda

- White-tailed Tropicbird, Phaethon lepturus

AEQUORNITHES Mayr, 2011

The remainder of the Ardeae are in the waterbird clade, Aequornithes. Gibb et al. (2013) use the term “water-carnivore” to describe the birds in this clade. The Aequornithes include 8 closely related orders: Gaviiformes (loons), Sphenisciformes (penguins), Procellariiformes (petrels and shearwaters), Ciconiiformes (storks), Suliformes (frigatebirds, boobies, cormorants, darters), Plataleiformes (ibis), Pelecaniformes (pelicans, hamerkop, shoebill), and Ardeiformes (herons).

There is a lot of support for grouping these birds together (e.g., Cracraft et al, 2004; Ericson et al., 2006a; Gibb et al., 2007, 2013; Hackett et al, 2008; Morgan-Richards et al, 2008), Jarvis et al. (2014).

GAVIIFORMES Coues 1903

Gaviiformes has been attributed to Wetmore & Miller, 1926, but Coues had already used Gaviae as a suborder in the second edition (1903) of his “Key to North American Birds” (pg. 1047). The term Colymbiformes has also been used. However, the ICZN eventually suppressed the genus Colymbus due to confusion about whether it applied to loons or grebes. Because of this, I have not tried to attribute priority to some earlier form of the order based on Colymbus, even though some case may be unambiguous. An account of this may be found on Wikipedia's Loon page.

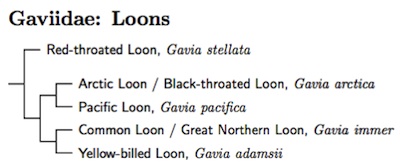

Sprengelmeyer (2014) found that the Red-throated Loon is very distantly separated from the other loons. He estimated the age of the most recent common ancestor as 21.4 million years ago, whereas the most recent common ancestor for the other four loons was only estimated at 8.2 million years ago.

Gaviidae: Loons J.A. Allen, 1897 (1840)

1 genus, 5 species HBW-1

- Red-throated Loon, Gavia stellata

- Arctic Loon / Black-throated Loon, Gavia arctica

- Pacific Loon, Gavia pacifica

- Common Loon / Great Northern Loon, Gavia immer

- Yellow-billed Loon, Gavia adamsii

SPHENISCIFORMES Huxley, 1867

Spheniscidae: Penguins Bonaparte, 1831

6 genera, 19 species HBW-1

The penguin taxonomy follows Baker et al. (2006). Ksepka and Thomas (2012) add some morphological data. They obtained an almost identical topology, differing only in the branching order within Eudyptes.

Although the members of the pairs Macaroni/Royal and Snares/Fiordland are considered separate biological species, the pair Little/White-flippered are not. Christidis and Boles (2008) opined that it was premature to split them, and subsequent analysis have proven them correct. The complicated situation of the Little Penguin is analyzed in detail by Puecker et al. (2009), and I suspect it is not the last word on this. They found two clades, as did previous workers. However, they sampled many more penguins and found the clades did not divide as expected. In particular, there is no support for treating the White-flippered Penguin, Eudyptula minor albosignata as a separate species. Rather, there is a mostly Australian clade (with some New Zealand birds mostly from Otago and Omaru), and a clade covering the rest of New Zealand. Although most of the birds at Omaru seem to group with the Australian E. m. novaehollandiae, not all do. It appears likely that the type of E. m. minor, which is from Dusky Sound, belongs to the New Zealand clade. The significance of the presence of Australian clade birds at Otago/Omaru is yet to be fully understood. E.g., is there interbreeding? If so, how much? Although some uncertainty remains, it looks like two species are involved. The name Little Penguin has been official in Australia for some time, while Blue Penguin has been used in New Zealand, so it makes sense to call them Little Penguin, Eudyptula novaehollandiae, and Blue Penguin, Eudyptula minor.

More recently, Grosser et al. (2015), studying DNA from modern penguins, found that the Austalian lineage penguins in New Zealand were recent arrivals, probably within the last 1500 years. Then Grosser et al. (2016) sampled bones from 146 prehistoric penguins found in New Zealand. The bones prior to 1500 AD all came from Blue Penguins. The Australian lineage Little Penguins did not show up until sometime after 1500. They speculate that a population decline of the native Blue Penguins following the arrival of humans created an opening for Little Penguins to colonize the island.

The Macaroni/Royal and Snares/Fiordland pairs breed on different islands. The differences in appearance and DNA to are sufficient to allow treatment as separate species. In fact, the DNA difference seems to be less than between the Eudyptula clades (Baker et al., 2006), but the Eudyptula plumage differences are smaller and the situation on the breeding grounds is unclear.

Jouventin et al. (2006) make a good case for splitting Rockhopper Penguin into two biological species. I did not find the case for a three-way split compelling (Banks et al, 2006).

- King Penguin, Aptenodytes patagonicus

Click for Penguin tree - Emperor Penguin, Aptenodytes forsteri

- Adelie Penguin, Pygoscelis adeliae

- Gentoo Penguin, Pygoscelis papua

- Chinstrap Penguin, Pygoscelis antarcticus

- Little Penguin, Eudyptula novaehollandiae

- Blue Penguin, Eudyptula minor

- Humboldt Penguin, Spheniscus humboldti

- Galapagos Penguin, Spheniscus mendiculus

- African Penguin / Jackass Penguin, Spheniscus demersus

- Magellanic Penguin, Spheniscus magellanicus

- Yellow-eyed Penguin, Megadyptes antipodes

- Erect-crested Penguin, Eudyptes sclateri

- Royal Penguin, Eudyptes schlegeli

- Macaroni Penguin, Eudyptes chrysolophus

- Fiordland Penguin, Eudyptes pachyrhynchus

- Snares Penguin, Eudyptes robustus

- Rockhopper Penguin / Southern Rockhopper Penguin, Eudyptes chrysocome

- Tristan Penguin / Northern Rockhopper Penguin, Eudyptes moseleyi

PROCELLARIIFORMES Fürbringer, 1888

The arrangement of the Procellariiforme families follows Prum et al. (2015). A number of sources have been consulted concerning the species sequence. Austin (1996), Austin et al. (2004), Kennedy and Page (2002) and Penhallurick and Wink (2004) were generally useful in organizing the Procellariiformes. Concerning the latter, the comments by Rheindt and Austin (2005) should be noted. Prum et al. (2015), Welch et al. (2014), and Gangloff et al. (2012) were helpful concerning the Procellariidae.

Diomedeidae: Albatrosses G.R. Gray, 1840

4 genera, 21 species HBW-1

Traditionally, the 24 recognized albatross taxa have been grouped into 13 species.

Traditional Albatross Species Limits

24 taxa, 13 species

- Laysan Albatross, Phoebastria immutabilis

- Black-footed Albatross, Phoebastria nigripes

- Waved Albatross, Phoebastria irrorata

- Short-tailed Albatross, Phoebastria albatrus

- Royal Albatross, Diomedea epomophora

- Diomedea epomophora sanfordi

- Diomedea epomophora epomophora

- Wandering Albatross, Diomedea exulans

- Diomedea exulans dabbenena

- Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis

- Diomedea exulans antipodensis

- Diomedea exulans gibsoni

- Diomedea exulans exulans

- Sooty Albatross, Phoebetria fusca

- Light-mantled Albatross, Phoebetria palpebrata

- Yellow-nosed Albatross, Thalassarche chlororhynchos

- Thalassarche chlororhynchos chlororhynchos

- Thalassarche chlororhynchos carteri

- Grey-headed Albatross, Thalassarche chrysostoma

- Black-browed Albatross, Thalassarche melanophris

- Thalassarche melanophris melanophris

- Thalassarche melanophris impavida

- Buller's Albatross, Thalassarche bulleri

- Thalassarche bulleri bulleri

- Thalassarche bulleri platei

- Shy Albatross, Thalassarche cauta

- Thalassarche cauta cauta

- Thalassarche cauta steadi

- Thalassarche cauta eremita

- Thalassarche cauta salvini

Robertson and Nunn (1998) suggested a radical new taxonomy for albatrosses, elevating all 24 taxa to species level. This has caused a certain amount of controversy, and has not been universally accepted (e.g., Penhallurick and Wink, 2004; Penhallurick, 2012). The 4th edition of the highly regarded Howard and Moore checklist (Dickinson and Remsen, 2013) also continues to follow traditional albatross taxonomy. Their version is shown above.

Nonetheless, many other sources have moved toward the Robertson and Nunn taxonomy, and the TiF list uses a 21 species version. IOC 3.3 uses the same 21 species list as TiF. BirdLife International (ver. 5) additionally splits T. cauta and T.steadi for 22 species. The AOU's SACC has adopted the 3-way split of Thalassarche cauta used here (see proposals #155 and #255. Clements 6.7 accepts only this split and uses a 15 species list. The SACC also considered splitting Diomedea exulans into 4 species (see proposal #388). This was unable to gain the required 2/3's majority (the vote was 6-4 in favor of the split). Penhallurick (2012) makes a case for retaining the traditional classification.

How to treat slightly differentiated allopatric taxa, where the breeding ranges do not overlap, is often a thorny issue. If you read SACC proposal #388, you will see just how contentious it is.

My take on it is that there is some evidence of restricted gene flow between many of these taxa—a sign of legitimate biological species. Although the evidence is a long way from being convincing, I think it is enough to barely tip the scale in favor of the 21-species treatment below, at least for the present.

Burg and Croxall (2004), Bried et al. (2007), and Rains et al. (2011) provided support for most of the Robertson and Nunn splits in the Wandering Albatross group (except for D. antipodensis gibsoni), while Burg and Croxall (2001) examined the Black-browed/Gray-headed Albatross group. The Shy Albatrosses were studied by Abbott and Double (2003a, b). Interestingly, the Wandering Albatross in the narrow sense remains widespread even after the other taxa in the group (Tristan, Antipodes, and Amsterdam Albatrosses) are split off.

The phylogeny used here is based on Nunn and Stanley (1998) and Chambers et al. (2009). Finally, the term platei is often used for the northern populations of Buller's Albatross. It is said to refer instead to a juvenile of the southern population, in which case a new name is needed for the northern population (e.g., Chambers et al., 2009).

- Waved Albatross, Phoebastria irrorata

Click for Albatross tree - Short-tailed Albatross, Phoebastria albatrus

- Laysan Albatross, Phoebastria immutabilis

- Black-footed Albatross, Phoebastria nigripes

- Northern Royal Albatross, Diomedea sanfordi

- Southern Royal Albatross, Diomedea epomophora

- Tristan Albatross, Diomedea dabbenena

- Antipodean Albatross, Diomedea antipodensis

- Amsterdam Albatross, Diomedea amsterdamensis

- Wandering Albatross, Diomedea exulans

- Sooty Albatross, Phoebetria fusca

- Light-mantled Albatross, Phoebetria palpebrata

- Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross, Thalassarche chlororhynchos

- Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross, Thalassarche carteri

- Gray-headed Albatross, Thalassarche chrysostoma

- Black-browed Albatross, Thalassarche melanophris

- Campbell Albatross, Thalassarche impavida

- Buller's Albatross, Thalassarche bulleri

- White-capped Albatross / Shy Albatross, Thalassarche cauta

- Chatham Albatross, Thalassarche eremita

- Salvin's Albatross, Thalassarche salvini

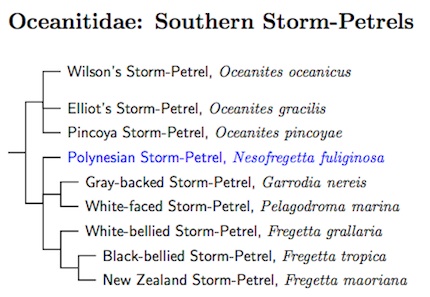

Oceanitidae: Southern Storm-Petrels Forbes, 1882

5 genera, 9 species Not HBW Family

The split of the Storm-Petrels into two families was suggested by Nunn and Stanley (1998). See also Hackett et al. (2008) and Prum et al. (2015).

I've added the Pincoya Storm-Petrel, Oceanites pincoyae, described by Harrison et al. (2013).

I've also added the New Zealand Storm-Petrel, which was rediscovered in 2003 (Gaskin and Baird, 2005; Stephenson et al, 2008a). Details of the capture of one are on the Pterodroma Pelagics web site. Some uncertainty remained as to its identity after the initial reports, but a comparison with museum specimens (Stephenson et al, 2008b) removed any doubt that it was a New Zealand Storm-Petrel. A recent genetic analysis by Robertson et al. (2011), based partly on data from Nunn and Stanley (1998), showed that it belongs in genus Fregetta rather than the monotypic Pealeornis.

Robertson et al. (2011) also found that the Fregetta race leucogaster, often considered a subspecies of the White-bellied Storm-Petrel, is actually much more closely related to the Black-bellied Storm-Petrel. Whether it is a subspecies or distinct species is unclear at this point.

- Wilson's Storm-Petrel, Oceanites oceanicus

- Elliot's Storm-Petrel, Oceanites gracilis

- Pincoya Storm-Petrel, Oceanites pincoyae

- Polynesian Storm-Petrel, Nesofregetta fuliginosa

- Gray-backed Storm-Petrel, Garrodia nereis

- White-faced Storm-Petrel, Pelagodroma marina

- White-bellied Storm-Petrel, Fregetta grallaria

- Black-bellied Storm-Petrel, Fregetta tropica

- New Zealand Storm-Petrel, Fregetta maoriana

Hydrobatidae: Northern Storm-Petrels Mathews, 1912-13 (1865)

4 genera, 17 species HBW-1

The Hydrobatidae have been rearranged based on Nunn and Stanley (1998) and Penhallurick and Wink (2004). This entails moving the Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel, Oceanodroma furcata, to the genus Hydrobates. Since O. furcata is the type species of Oceanodroma, it is helpful to give other genus names to the other three Hydrobatidae clades. Fortunately, the supply of available names is more than adequate. Those that are relevant are Cymochorea (Coues 1864, type leucorhoa) and Halocyptena (Coues 1864, type microsoma), and Thalobata (Matthews and Hallstrom 1943, type castro).

I've grouped melania and matsudairae together as they are sometimes considered conspecific. That pair is sister to the microsoma/tethys pair, and all join Halocyptena. I've also grouped two other possibly conspecific pairs, tristrami and markhami, and monorhis and leucorhoa. Homochroa might be close to the leucorhoa group. All of these go in Cymochorea. It's not clear where hornbyi goes, and it is provisionally placed somewhere in Cymochorea too.

That brings us to the basal group, the contentious Band-rumped (Madeiran) Storm-Petrel, Thalobata castro. Traditionally, it has been thought almost undifferentiated across the Atlantic and Pacific. Now we find that the genes reveal both substantial geographic and seasonal structure, enough that some recommend dividing it into a number of species (see Bolton (2007); Bolton et al., 2008; Friesen et al., 2007; Smith and Friesen, 2007; Smith et al., 2007).

In several locations, Band-rumped Storm-Petrel breeds in both the hot and cool seasons. Recent studies have found that the hot-season population is different from the cool-season population (e.g., Bolton, 2007; Frisen et al., 2007). The following table shows the island groups where Band-rumped Storm-Petrels breed, the season they breed, and applicable subspecific names. There may also be a population breeding on or near Sao Tome, but breeding sites have never been located. Further, it is unknown how closely the St. Helena and Ascension birds are related.

The breeding locations and seasons are:

| Location | Season | Subspecies | TiF Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascension & St. Helena Islands | hot | helena | castro |

| Azores | hot | monteiroi | monteiroi |

| Azores Madeira Canaries Berlengas |

cool both cool cool |

castro | castro |

| Cape Verde Islands | protracted (cool) | jabejabe | jabejabe |

| Galapagos Islands | both | bangsi | cryptoleucura |

| Hawaiian Islands | hot | cryptoleucura | cryptoleucura |

| Japan | hot | kumagai | cryptoleucura |

Because they breed in the same location, there is a tendency to think of these as sympatric populations. Since they don't interbreed, they must be distinct species. QED.

Some have even suggested that castro be restricted to the birds breeding in Madiera (Desertas and Selvagem) during the hot season. The rest would be separated as Grant's Storm-Petrel, which does not yet have a scientific name. I find this hard to swallow. Based on Friesen et al. (2007) and Smith et al. (2007), the genetic distances appear to be quite small. Any separation between them is quite recent, perhaps within the Holocene.

Although Friesen et al. (2007) suggest the ancestral birds bred in the hot season, I don't really see this. The Cape Verde population is sister to the others and has a prolonged breeding season. If the ancestral population spread from there, one could easily see it adapting to local conditions that variously support breeding in the hot and/or cool seasons.

This suggests that considering them as sympatric gives the wrong impression. Rather, these populations occupy different niches that in some cases are separated temporally rather than geographically. They are better regarded as being adjacent (or even isolated) rather than overlapping.

This changes the picture. If we think of these populations as potential allospecies, they may not make the grade. There's not much differentiation. More evidence is needed, and there is more for some populations. Bolton (2007) used tape playback to explore whether there are pre-mating barriers to interbreeding. He investigated populations on the Cape Verde, Galapagos, and Azores islands. Although birds responded to calls of birds from their own islands, response to birds from other islands was weak and often no more than to unrelated control species.

This suggests that at least the subspecies tested — jabejabe (Cape Verde), bangsi (Galapagos), monteiroi (Azores hot season), and castro (Azores cold season only) — are distinct biological species. What about the other populations? We first consider the remaining Atlantic populations. Table 3 in Smith et al. (2007) addresses this issue. It shows that the northern Atlantic populations other than monteiroi are quite closely related (estimated divergence times from 100(!) to 17,000 years). Accordingly, I keep them all in T. castro. It also suggests that the birds from Ascension (and St. Helena?) are fairly close to the main populations of castro (divergence time 15,000-30,000 years, as opposed to about 100,000 years between monteiroi and castro, and 200,000-300,000 between jabejabe and either castro or monteiroi). Accordingly, I also treat helena as a form of T. castro.

|

| Click for Storm-Petrel tree |

|---|

That brings us to the Pacific populations. We start with the hot and cool season breeders at the Galapagos Islands. Bolton (2007) found they did not respond to the calls of band-rumped storm-petrels from the Atlantic. Moreover, Smith et al. (2007) found divergence times of over 200,000 years between them and the Atlantic breeders. Finally, Smith and Friesen (2007) found only weak evidence that these involve a cryptic species, and suggested they are only as distinct from each other as subspecies. Here they are treated as part of the same species, distinct from the Atlantic species. The analysis of Freisen et al. (2007) found that the Japanese and Galapagos breeders form a separate clade. Returning to Table 3 of Smith et al. (2007), we also see that the Hawaiian breeders belong in this group. Moreover, the divergence time of 150,000-200,000 years does not compel us to treat them as separate species from each other (absent further evidence). Accordingly, I treat the Pacific populations of band-rumped storm-petrels as a single species, T. cryptoleucura, including bangsi (Galapagos) and kumagai (Japan).

When all is said and done, I treat the band-rumped storm-petrels as 4 species. These species are separated not only by breeding location, but by whether they breed in the hot or cool season. In some cases there is little genetic differentiation between hot or cool season breeders, or across islands. When there is no other evidence they form separate species, those populations are lumped together, either as T. castro or T. cryptoleucura.

- Cape Verde Storm-Petrel, Thalobata jabejabe

- “Pacific Storm-Petrel”, Thalobata cryptoleucura

- Monteiro's Storm-Petrel, Thalobata monteiroi

- Band-rumped Storm-Petrel / Madeiran Storm-Petrel, Thalobata castro

- Least Storm-Petrel, Halocyptena microsoma

- Wedge-rumped Storm-Petrel, Halocyptena tethys

- Black Storm-Petrel, Halocyptena melania

- Matsudaira's Storm-Petrel, Halocyptena matsudairae

- European Storm-Petrel / British Storm-Petrel, Hydrobates pelagicus

- Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel, Hydrobates furcatus

- Ringed Storm-Petrel / Hornby's Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea hornbyi

- Markham's Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea markhami

- Tristram's Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea tristrami

- Guadalupe Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea macrodactyla

- Ashy Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea homochroa

- Swinhoe's Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea monorhis

- Leach's Storm-Petrel, Cymochorea leucorhoa

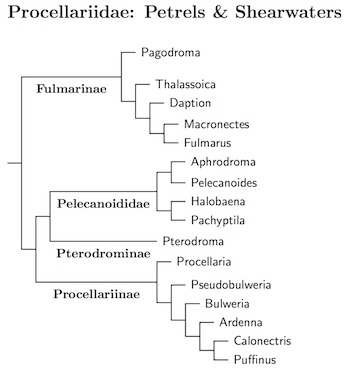

Procellariidae: Petrels, Shearwaters Leach, 1820

16 genera, 97 species HBW-1

|

| Click for Procellariidae tree |

|---|

The higher-level relationships within the Procellariidae remain somewhat murky. I've used Prum et al. (2015) as a backbone, and rerooted the tree from Welch et al. (2014) to provide the rest of the structure. The result is also compatible with Gangloff et al. (2012). The taxa shown in brown are subspecies that may deserve species status.

In the new arrangement, the Fulmarinae are the basal group.

The Northern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis, has been split into the Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis and the Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii, based on Kerr and Dove (2013), who estimated their most recent common ancestor ocurred about 3 million years ago. Although the separation was clear enough in mitochondrial DNA, it didn't show in nuclear DNA. Presumably they simply looked a slow-evolving gene.

Fulmarinae: Fulmars Bonaparte, 1853

- Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea

- Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica

- Cape Petrel, Daption capense

- Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus

- Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli

- Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides

- Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis

- Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii

Pelecanoidinae: Diving-Petrels and Prions G.R. Gray, 1871 (1850)

The Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris is rather uncertainly placed in the basal position here.

The Pelecanoides diving-petrels are traditionally considered a separate family from the petrels (Procellariidae). In many ways, including size, shape, and flight style, they are a southern counterpart of the smaller auks. However, Prum et al. (2015) found them embedded within the Procellariidae.

The Prions and Blue Petrel form the remainder of this group.

- Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris

- Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii

- Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix

- South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus

- Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani

- Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea

- Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur

- Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris

- Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata

- Salvin's Prion, Pachyptila salvini

- Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata

- Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri

Pterodrominae: Gadfly Petrels Verheyen, 1958 (1856)

Among the Petrodroma, I've elevated the Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma desertas to species status based on Zino et al. (2008) and Jesus et al. (2009). Note that the extinct St. Helena Petrel, Pterodroma rupinarum has now been sequenced by Welch et al. (2014) and found to belong to Pterodroma rather than Pseudobulweria.

- Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca

- Gould's Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera

- Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes

- Cook's Petrel, Pterodroma cookii

- Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi's Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana

- Stejneger's Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris

- Pycroft's Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti

- Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis

- Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae

- Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba

- Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta

- Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera

- White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii

- Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata

- Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow

- Zino's Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira

- Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma deserta

- Fea's Petrel / Cape Verde Petrel, Pterodroma feae

- St. Helena Petrel, Pterodroma rupinarum

- Black-winged Petrel, Pterodroma nigripennis

- Chatham Petrel, Pterodroma axillaris

- Providence Petrel, Pterodroma solandri

- Trindade Petrel, Pterodroma arminjoniana

- Kermadec Petrel, Pterodroma neglecta

- Henderson Petrel, Pterodroma atrata

- Herald Petrel, Pterodroma heraldica

- Mottled Petrel, Pterodroma inexpectata

- Murphy's Petrel, Pterodroma ultima

- Barau's Petrel, Pterodroma baraui

- Galapagos Petrel, Pterodroma phaeopygia

- Hawaiian Petrel, Pterodroma sandwichensis

- Juan Fernandez Petrel, Pterodroma externa

- Vanuatu Petrel, Pterodroma occulta

- White-necked Petrel, Pterodroma cervicalis

Procellariinae: Petrels and Shearwaters Leach, 1820

The division of Puffinus into species is based on Austin et al. (2004). Since it is doubtful that the two clades of Puffinus (here called Ardenna and Puffinus) are more closer related to each other than to Calonectris, they are placed in separate genera.

The Calonectris shearwaters have been studied by Gómez-Díaz et al. (2006). They found that the three Atlantic taxa, borealis, diomedea, and edwardsii, form distinct clades that are roughly equidistant genetically, with diomedea perhaps closer to edwardsii. Their study of morphology found diomedea and borealis very close, with edwardsii somewhat more distant. I've treated this as an unresolved trichotomy on the tree. Following the recommendations of Sangster et al. (2012), the three Atlantic taxa are considered distinct species. The Mediterranean population takes the name Scopoli's Shearwater, Calonectris diomedea, the Cape Verde population becomes Cape Verde Shearwater, Calonectris edwardsii, while Cory's Shearwater is now restriced to Calonectris borealis.

The Cory's/Scopoli's split is of potential interest in the ABA area as there are several specimens of Scopoli's from New York in the early 20th century (Bull, 1974). More recently, Scopoli's has been photographed off the North Carolina and Florida coasts.

That brings us to the Puffinus species swamp. Although Austin et al. (2004) went a long way toward clarifying matters, not all of their results were conclusive, and an inability to extract DNA from certain specimens meant that some taxa were not included (specimens of auricularis, bannermani, and gunax did not yield usable DNA, while heinrothi was not sampled at all). They only examined a single gene: cytochrome-b. Although cytochrome-b is usually pretty reliable at this level of analysis, we would be happier if it were confirmed by a multi-gene analysis. Moreover, some clades have weak support, and additional genes might clarify the situation there.

Several extinct Puffinus taxa have been identified. Olson (2010) makes a strong osteological case that fossil bones from Bermuda previously named P. parvus actually belong to Boyd's Shearwater, P. boydi. It appears likely it was extirpated from Bermuda following human occupation. Interestingly, Audubon's Shearwater then briefly colonized the island, but was extirpated in the 20th century. Ramirez et al. (2010) attempted to examine DNA from the extinct Lava Shearwater, P. olsoni, and the Dune Shearwater, P. holeae. Although they were successful with with olsoni, which is probably best regarded as a form of the Manx Shearwater, P. puffinus, they were unsuccessful with holeae.

One interesting thing about the various Puffinus races is the limited overlap in breeding range. Only the Manx Shearwater, P. puffinus even shares an island with other types of Puffinus. This happens even when two or more Puffinus are present in the same area. This helps strengthen the case for species status of a number of races.

Heinroth's Shearwater, Puffinus heinrothi, differs in plumage from most of Puffinus (in our narrow sense). No DNA information is available. It's probably relatively basal and I've listed it first to highlight the uncertainty.

Of the taxa we have DNA for, the Christmas (nativitatis) and Galapagos (subalaris) Shearwaters are basal. They may be more closely related to each other than the rest of Puffinus, but this is not entirely clear (compare Austin et al., 2004 and Ramirez et al., 2010). In any event, the remaining species form a clade, with Hutton's (huttoni) and Fluttering (gavia) Shearwaters of New Zealand grouping together. All of these taxa are monotypic.

The rest of the Puffinus shearwaters are more tightly grouped, but divide into two parts: an Audubon/Manx group and a Tropical Shearwater group. However, there is some ambiguity in the analysis, and the Manx group may actually be basal (or two basal groups). In any event, the inferred timing of the split between Manx (puffinus), Yelkouan (yelkouan), and Balearic (mauretanicus) Shearwaters post-dates the refilling of the Mediterranean Sea about 5 million years ago. Further, the split between the Atlantic Manx/Audubon two clades may have been driven by the closing of the Isthmus of Panama which completed about 3 million years ago. If the isthmus hypothesis is correct, I wonder whether there was one widespread small shearwater prior to the cleavage of the oceans, or whether groups separated on either side of the isthmus then diversified east or west into their respective seas, finally meeting again near the Tropic of Capricorn north of New Zealand.

Besides the Manx group, the Atlantic part includes the Little/Audubon's group. The southerly Little Shearwater (assimilis), includes assimilis, tunneyi, kermadecensis, and haurakiensis. The subspecies elegans has been raised to species level as Subantarctic Shearwater. The northerly Audubon's group includes 4 taxa: Audubon's Shearwater (P. lherminieri lherminieri and P. l. loyemilleri (if valid)), Barolo Shearwater (P. baroli, and Boyd's Shearwater, P. boydi.

The last group contains the rest of the shearwaters. Before proceeding, we consider the Townsend's Shearwater complex, which has been studied by Martínez Gómez et al. (2015). They found that auricularis and newelli are not genetically distinct. Accordingly, Newell's Shearwater, Puffinus newelli, is lumped into Townsend's Shearwater, Puffinus auricularis. However, the third subspecies, myrtae, is sufficiently distinct to elevate to a species, Rapa Shearwater, Puffinus myrtae.

The remaining shearwaters breed in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas. The first portion is relatively clear-cut. It includes the recently discovered Bryan's Shearwater, Puffinus bryani (Pyle et al., 2011), the monotypic Black-vented (P. opisthomlelas), and Townsend's (P. auricularis, including newelli) Shearwaters, and Rapa Shearwater (P. myrtae).

The 10 remaining taxa appear to be closely related. The unsampled Bannerman's Shearwater, P. bannermani, of Japan is treated as a separate species, as is the Persian Shearwater (P. persicus plus temptator). The remaining races are very closely related and are treated as a single species: Tropical Shearwater, P. bailloni. However, this species is sometimes split further into a Pacific group, Atoll Shearwater (dichrous, plus polynesiae, colstoni, nicolae, and presumably gunax), leaving bailloni and the possibly redundant atrodorsalis as Baillon's Shearwater.

- Gray Petrel, Procellaria cinerea

- White-chinned Petrel, Procellaria aequinoctialis

- Spectacled Petrel, Procellaria conspicillata

- Parkinson's Petrel / Black Petrel, Procellaria parkinsoni

- Westland Petrel, Procellaria westlandica

- Mascarene Petrel, Pseudobulweria aterrima

- Fiji Petrel, Pseudobulweria macgillivrayi

- Tahiti Petrel, Pseudobulweria rostrata

- Beck's Petrel, Pseudobulweria becki

- Bulwer's Petrel, Bulweria bulwerii

- Olson's Petrel, Bulweria bifax

- Jouanin's Petrel, Bulweria fallax

- Pink-footed Shearwater, Ardenna creatopa

- Flesh-footed Shearwater, Ardenna carneipes

- Wedge-tailed Shearwater, Ardenna pacifica

- Buller's Shearwater, Ardenna bulleri

- Short-tailed Shearwater, Ardenna tenuirostris

- Sooty Shearwater, Ardenna grisea

- Great Shearwater, Ardenna gravis

- Streaked Shearwater, Calonectris leucomelas

- Cory's Shearwater, Calonectris borealis

- Scopoli's Shearwater, Calonectris diomedea

- Cape Verde Shearwater, Calonectris edwardsii

- Heinroth's Shearwater, Puffinus heinrothi

- Christmas Shearwater / Kirimati Shearwater, Puffinus nativitatis

- Galapagos Shearwater, Puffinus subalaris

- Fluttering Shearwater, Puffinus gavia

- Hutton's Shearwater, Puffinus huttoni

- Manx Shearwater, Puffinus puffinus

- Balearic Shearwater, Puffinus mauretanicus

- Yelkouan Shearwater, Puffinus yelkouan

- Little Shearwater, Puffinus assimilis

- Subantarctic Shearwater, Puffinus elegans

- Audubon's Shearwater, Puffinus lherminieri

- Barolo Shearwater, Puffinus baroli

- Boyd's Shearwater, Puffinus boydi

- Bryan's Shearwater, Puffinus bryani

- Black-vented Shearwater, Puffinus opisthomelas

- Townsend's Shearwater, Puffinus auricularis

- Rapa Shearwater, Puffinus myrtae

- Persian Shearwater, Puffinus persicus

- Tropical Shearwater, Puffinus bailloni

- Bannerman's Shearwater, Puffinus bannermani

- Marabou / Marabou Stork, Leptoptilos crumenifer

Click for Ciconiidae

species tree - Lesser Adjutant, Leptoptilos javanicus

- Greater Adjutant, Leptoptilos dubius

- Abdim's Stork, Ciconia abdimii

- Woolly-necked Stork, Ciconia episcopus

- Storm's Stork, Ciconia stormi

- Black Stork, Ciconia nigra

- Maguari Stork, Ciconia maguari

- White Stork, Ciconia ciconia

- Oriental Stork, Ciconia boyciana

- Jabiru, Jabiru mycteria

- Black-necked Stork, Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus

- Saddle-billed Stork, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis

- Asian Openbill, Anastomus oscitans

- African Openbill, Anastomus lamelligerus

- Wood Stork, Mycteria americana

- Yellow-billed Stork, Mycteria ibis

- Milky Stork, Mycteria cinerea

- Painted Stork, Mycteria leucocephala

- Lesser Frigatebird, Fregata ariel

- Ascension Frigatebird, Fregata aquila

- Magnificent Frigatebird, Fregata magnificens

- Great Frigatebird, Fregata minor

- Christmas Frigatebird, Fregata andrewsi

- Abbott's Booby, Papasula abbotti

- Northern Gannet, Morus bassanus

- Cape Gannet, Morus capensis

- Australasian Gannet, Morus serrator

- Red-footed Booby, Sula sula

- Brown Booby, Sula leucogaster

- Blue-footed Booby, Sula nebouxii

- Peruvian Booby, Sula variegata

- Masked Booby, Sula dactylatra

- Nazca Booby, Sula granti

- Anhinga, Anhinga anhinga

- African Darter, Anhinga rufa

- Oriental Darter, Anhinga melanogaster

- Australasian Darter, Anhinga novaehollandiae

- Long-tailed Cormorant / Reed Cormorant, Microcarbo africanus

Click for Cormorant tree - Crowned Cormorant, Microcarbo coronatus

- Pygmy Cormorant, Microcarbo pygmeus

- Little Cormorant, Microcarbo niger

- Little Pied Cormorant, Microcarbo melanoleucos

- Red-legged Cormorant, Poikilocarbo gaimardi

- Spectacled Cormorant / Pallas's Cormorant, Phalacrocorax perspicillatus

- Brandt's Cormorant, Phalacrocorax penicillatus

- Pelagic Cormorant, Phalacrocorax pelagicus

- Red-faced Cormorant, Phalacrocorax urile

- Bank Cormorant, Phalacrocorax neglectus

- Cape Cormorant, Phalacrocorax capensis

- White-breasted Cormorant, Phalacrocorax lucidus

- Great Cormorant, Phalacrocorax carbo

- Japanese Cormorant, Phalacrocorax capillatus

- Socotra Cormorant, Phalacrocorax nigrogularis

- Spotted Shag, Phalacrocorax punctatus

- Pitt Shag, Phalacrocorax featherstoni

- Indian Cormorant, Phalacrocorax fuscicollis

- Little Black Cormorant, Phalacrocorax sulcirostris

- Black-faced Cormorant, Phalacrocorax fuscescens

- Pied Cormorant / Australian Pied Cormorant, Phalacrocorax varius

- European Shag, Phalacrocorax aristotelis

- Flightless Cormorant, Phalacrocorax harrisi

- Neotropic Cormorant, Phalacrocorax brasilianus

- Double-crested Cormorant, Phalacrocorax auritus

- Magellan Cormorant / Rock Shag, Phalacrocorax magellanicus

- Guanay Cormorant, Phalacrocorax bougainvillii

- Bounty Shag, Phalacrocorax ranfurlyi

- New Zealand Shag, Phalacrocorax carunculatus

- Stewart Shag / Bronze Shag, Phalacrocorax chalconotus

- Chatham Shag, Phalacrocorax onslowi

- Auckland Shag, Phalacrocorax colensoi

- Campbell Shag, Phalacrocorax campbelli

- Falkland Cormorant, Phalacrocorax albiventer

- Imperial Cormorant / Imperial Shag, Phalacrocorax atriceps

- South Georgia Shag, Phalacrocorax georgianus

- Crozet Shag, Phalacrocorax melanogenis

- Antarctic Shag, Phalacrocorax bransfieldensis

- Kerguelen Shag, Phalacrocorax verrucosus

- Heard Island Shag, Phalacrocorax nivalis

- Macquarie Shag, Phalacrocorax purpurascens

- White Ibis / American White Ibis, Eudocimus albus

- Scarlet Ibis, Eudocimus ruber

- Sharp-tailed Ibis, Cercibis oxycerca

- Green Ibis, Mesembrinibis cayennensis

- Bare-faced Ibis, Phimosus infuscatus

- Plumbeous Ibis, Theristicus caerulescens

- Buff-necked Ibis, Theristicus caudatus

- Black-faced Ibis, Theristicus melanopis

- Glossy Ibis, Plegadis falcinellus

- White-faced Ibis, Plegadis chihi

- Puna Ibis, Plegadis ridgwayi

- Crested Ibis, Nipponia nippon

- Madagascan Ibis, Lophotibis cristata

- Northern Bald-Ibis, Geronticus eremita

- Southern Bald-Ibis, Geronticus calvus

- Olive Ibis, Bostrychia olivacea

- Sao Tome Ibis, Bostrychia bocagei

- Spot-breasted Ibis, Bostrychia rara

- Hadada Ibis, Bostrychia hagedash

- Wattled Ibis, Bostrychia carunculata

- Roseate Spoonbill, Platalea ajaja

- Yellow-billed Spoonbill, Platalea flavipes

- African Spoonbill, Platalea alba

- Eurasian Spoonbill, Platalea leucorodia

- Black-faced Spoonbill, Platalea minor

- Royal Spoonbill, Platalea regia

- Red-naped Ibis, Pseudibis papillosa

- White-shouldered Ibis, Pseudibis davisoni

- Giant Ibis, Pseudibis gigantea

- Reunion Ibis, Threskiornis solitarius

- African Sacred-Ibis, Threskiornis aethiopicus

- Malagasy Sacred-Ibis, Threskiornis bernieri

- Black-headed Ibis, Threskiornis melanocephalus

- Australian White Ibis, Threskiornis moluccus

- Straw-necked Ibis, Threskiornis spinicollis

- Hamerkop, Scopus umbretta

- Shoebill, Balaeniceps rex

- American White Pelican, Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

- Brown Pelican, Pelecanus occidentalis

- Peruvian Pelican, Pelecanus thagus

- Great White Pelican, Pelecanus onocrotalus

- Australian Pelican, Pelecanus conspicillatus

- Pink-backed Pelican, Pelecanus rufescens

- Dalmatian Pelican, Pelecanus crispus

- Spot-billed Pelican, Pelecanus philippensis

- Forest Bittern, Zonerodius heliosylus

- White-crested Tiger-Heron, Tigriornis leucolopha

- Rufescent Tiger-Heron, Tigrisoma lineatum

- Fasciated Tiger-Heron, Tigrisoma fasciatum

- Bare-throated Tiger-Heron, Tigrisoma mexicanum

- Boat-billed Heron, Cochlearius cochlearius

- Zigzag Heron, Zebrilus undulatus

- Eurasian Bittern, Botaurus stellaris

- Australasian Bittern, Botaurus poiciloptilus

- American Bittern, Botaurus lentiginosus

- Pinnated Bittern, Botaurus pinnatus

- Least Bittern, Ixobrychus exilis

- Stripe-backed Bittern, Ixobrychus involucris

- Black Bittern, Ixobrychus flavicollis

- Von Schrenck's Bittern, Ixobrychus eurhythmus

- Cinnamon Bittern, Ixobrychus cinnamomeus

- Dwarf Bittern, Ixobrychus sturmii

- Little Bittern, Ixobrychus minutus

- Yellow Bittern, Ixobrychus sinensis

- Black-backed Bittern, Ixobrychus dubius

- New Zealand Bittern, Ixobrychus novaezelandiae

- White-eared Night-Heron, Gorsachius magnificus

- Japanese Night-Heron, Gorsachius goisagi

- Malayan Night-Heron, Gorsachius melanolophus

- White-backed Night-Heron, Gorsachius leuconotus

- Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, Nyctanassa violacea

- Bermuda Night-Heron, Nyctanassa carcinocatactes

- Black-crowned Night-Heron, Nycticorax nycticorax

- Nankeen Night-Heron, Nycticorax caledonicus

- Ascension Night-Heron, Nycticorax olsoni

- Reunion Night-Heron, Nycticorax duboisi

- Mauritius Night-Heron, Nycticorax mauritianus

- Rodrigues Night-Heron, Nycticorax megacephalus

- Capped Heron, Pilherodius pileatus

- Whistling Heron, Syrigma sibilatrix

- Pied Heron, Egretta picata

- White-faced Heron, Egretta novaehollandiae

- Tricolored Heron, Egretta tricolor

- Reddish Egret, Egretta rufescens

- Black Heron, Egretta ardesiaca

- Slaty Egret, Egretta vinaceigula

- Pacific Reef-Heron, Egretta sacra

- Chinese Egret, Egretta eulophotes

- Dimorphic Egret, Egretta dimorpha

- Western Reef-Heron, Egretta gularis

- Little Egret, Egretta garzetta

- Snowy Egret, Egretta thula

- Little Blue Heron, Egretta caerulea

- Agami Heron, Agamia agami

- Green Heron, Butorides virescens

- Lava Heron, Butorides sundevalli

- Striated Heron, Butorides striata

- Squacco Heron, Ardeola ralloides

- Indian Pond-Heron, Ardeola grayii

- Chinese Pond-Heron, Ardeola bacchus

- Javan Pond-Heron, Ardeola speciosa

- Malagasy Pond-Heron, Ardeola idae

- Rufous-bellied Heron, Ardeola rufiventris

- Cattle Egret, Bubulcus ibis

- Intermediate Egret, Mesophoyx intermedia

- Great Egret, Casmerodius albus

- American Egret, Casmerodius egretta

- Gray Heron, Ardea cinerea

- Great Blue Heron, Ardea herodias

- Cocoi Heron, Ardea cocoi

- White-necked Heron, Ardea pacifica

- Black-headed Heron, Ardea melanocephala

- Humblot's Heron, Ardea humbloti

- White-bellied Heron, Ardea insignis

- Great-billed Heron, Ardea sumatrana

- Goliath Heron, Ardea goliath

- Purple Heron, Ardea purpurea

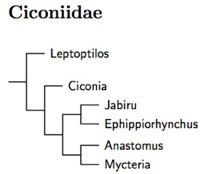

CICONIIFORMES Bonaparte, 1854

Although Hackett et al. (2008) found that the storks were basal in the remaining Ardeae (after the penguins and seabirds), Gibb et al. (2013) placed them next to the herons. However, Jarvis et al. (2014) came up with a different arrangement of the taxa, casting doubt on the Gibb et al. treatment. The latest analyses are from Prum et al. (2015) and Kuramoto et al. (2015), who both found the stocks to be basal in this group.

Slikas (1997) did not come to a definitive conclusion on how to arranged the genera of the Ciconiidae. I've adopted her maximum likelihood tree. However, it may not be correct, and there were indications that Ciconia itself may not be monophyletic.

Ciconiidae: Storks Sundevall, 1836

6 genera, 19 species HBW-1

SULIFORMES Sharpe 1891

AOU officially adopted the term Suliformes in the 51st supplement. Sharpe had previously used Sulae as a suborder. For that matter, he also had Fregatae and Phalacrocoraces as suborders. The Suliformes had previously been considered part of the Pelecaniformes, a tradition that dates back to their naming by Sharpe.

The Suliformes were traditionally considered part of the Pelecaniformes (as were the tropicbirds). After all, how likely was it that such unusual features as a totipalmate foot and gular pouch would arise independently? They also share the location of the salt-excreting gland and all lack an incubation patch. These similarities lead Linneaus to put all but the tropicbirds (which lack the gular pouch) in the same genus.

Fregatidae: Frigatebirds Degland & Gerbe, 1867 (1840)

1 genus, 5 species HBW-1

The frigatebird taxonomy follows Kennedy and Spencer (2004).

Sulidae: Gannets, Boobies Reichenbach, 1849 (1836)

3 genera, 10 species HBW-1

|

| Click for Sulidae tree |

|---|

Sulid taxonomy follows Patterson et al. (2011), which is similar to Friesen et al. (2002), except that Papasula is considered basal. The extinct Tasman Booby, often considered a separate species, is here considered a subspecies of the Masked Booby following Christidis and Boles (2008). More recently, Steeves et al. (2010) provides strong evidence for this treatment. They further argue that Sula dactylatra tasmani is identical with the still extant subspecies S. d. fullagari, in which case both should be referred to as S. d. tasmani.

Anhingidae: Anhingas Reichenbach, 1849 (1815)

1 genus, 4 species HBW-1

Phalacrocoracidae: Cormorants Reichenbach, 1849-50 (1836)

3 genera, 42 species HBW-1

The arrangement below is now based primarily on Kennedy and Spencer (2014). Previously, I had used the DNA analyses of Kennedy et al. (2000, 2001, 2009) and the osteological analysis of Siegel-Causey (1988), following Kennedy et al. in case of disagreement. You can click on the tree diagram for the phylogeny. The species in black were included in Kennedy and Spencer, while no DNA data is available for species marked in blue on the tree. In those cases, I've followed Sigel-Causey when possible. The paper by Kennedy et al. (2009) resolved the long-controversial status of the Flightless Cormorant. They found it is sister to the Neotropic and Double-crested Cormorants.

On the tree, I've included some of the available genus names that could be used to subdivide Phalacrocorax. Unless they are generally adopted, they are perhaps mostly best thought of as subgenera. However, the Red-legged Cormorant is so genetically distant and so distinct that I have moved it to Poikilocarbo.

Although work has been done on the phylogeny of the blue-eyed shag complex, the correct species limits remain murky. There are eight Phalacrocorax taxa involved: albiventer, atriceps, georgianus, melanogenis, bransfieldensis, verrucosus, purpurascens, and nivalis. Kennedy and Spencer (2014) found three clades in the group: (1) albiventer, atriceps, and georgianus; (2) melanogenis and bransfieldensis; (3) verrucosus, purpurascens, and nivalis, with clades (2) and (3) closer to each other than to clade (1). The genetic distances are close enough that these allopatric taxa could be considered one species.

Following SACC, the continental representatives of King Cormorant, Phalacrocorax albiventer are considered a color morph of the Imperial Cormorant, Phalacrocorax atriceps (aka Blue-eyed Shag). Rasmussen (1991) makes a strong case for this. The key points are in the abstract: frequent hybridization and non-assortative mating in the contact zones. The genetic distance as measured using allozymes also seems very small.

Kennedy and Spencer (2014) found that the King Cormorants from the Falklands are different from continental `albiventer' (labelled atriceps in the paper, and presumed a color morph). They don't seem to include any of the white-cheeked color morph of atriceps. They found atriceps to be sister to georgianus and the Falklands sample basal to both. Note that Rasmussen's (1991) arguments don't necessarily pertain to the Falklands birds. Because of this I treat the visually distinct King Cormorant of the Falklands as a separate species, Falkland Cormorant, Phalacrocorax albiventer (the type of albiventer is from the Falklands).

Antarctic Shag, Phalacrocorax bransfieldensis, and South Georgia Shag, Phalacrocorax georgianus, are split off as separate species (Siegel-Causey and Lefevre, 1989). They present evidence that the breeding range of the Antarctic Shag formerly included the area around Tierra del Fuego, part of the breeding range of P. atriceps. They argue that there is no sign of interbreeding, indicating they are separate biological species. Kennedy and Spencer (2014) found that the Antarctic Shag is more closely related to the Crozet Shag than the Imperial Cormorant. The South Georgia Shag seems distinct from the Imperial Cormorant, and is arguably also a separate species.

That still leaves 3 taxa to deal with. Unfortunately, there seems to be little solid information to work with. Christidis and Boles (2008) note all this, but consider these three taxa to be subspecies of P. atriceps. There is one piece of evidence. The genetic distance between purpurascens and albiventer is small enough for them to be a single species. However, it's also large enough to be different species. In HBW-1, Orta (1992) takes the opposite tack and splits them.

In version 2.17 I followed Christidis and Boles concerning melanogenis, nivalis, purpurascens. This left me with the same four species as Sibely and Monroe (1990). I gather I'm not the only one uncomfortable with that solution. It just doesn't make biogeographic sense to have birds breeding on the other side of the world lumped into atriceps when the physically closer taxa are considered separate species. In the absence of definitive information, this version follows Orta (1992) in considering them as three species.

PLATALEIFORMES Newton 1884

Although some analyses have indicated that the herons and ibises are sister clades, support has been weak. Gibb et al. (2013) studied the complete mitochondrial genome of 4 herons, 4 ibises, and related taxa. They found that the herons and ibises do not form a clade, and estimated that they have been separate lineages since the early Paleocene. Since there is uncertainty about their closest relatives, and each represents a truly ancient lineage, I treat them both in their own orders.

Kuramoto et al. (2015) have found evidence of early hybridization between ancient ibises and herons following the split of between the heron and pelican lineages. That would explain the conflicting results in earlier analyses.

Threskiornithidae: Ibises, Spoonbills Poche, 1904

13 genera, 35 species HBW-1

The traditional treatment of the ibises and spoonbills as sister subfamilies

is just wrong. The spoonbills are not the sister group of the ibises. Rather, they

are most closely related to Threskiornis and perhaps Pseudibis.

Krattinger's MA thesis (2010) shows this fact clearly. Chesser et al. (2010) is consistent

with this idea, and it already appeared in Sibley and Ahlquist (1990;

esp. Fig. 367). Oddly, Sibley and Ahlquist did not comment on it.

Perhaps they found it too unbelievable.

The traditional treatment of the ibises and spoonbills as sister subfamilies

is just wrong. The spoonbills are not the sister group of the ibises. Rather, they

are most closely related to Threskiornis and perhaps Pseudibis.

Krattinger's MA thesis (2010) shows this fact clearly. Chesser et al. (2010) is consistent

with this idea, and it already appeared in Sibley and Ahlquist (1990;

esp. Fig. 367). Oddly, Sibley and Ahlquist did not comment on it.

Perhaps they found it too unbelievable.

Interestingly, there had been other hints that the spoonbills should not be treated as a subfamily. Matheu and del Hoyo (1992=HBW-1) mention that the Eurasian Spoonbill has been known to hybridize with Black-headed Ibis,Threskiornis melanocephalus. Unfortunately, they did not make the connection with Sibley and Ahlquist's results.

Krattinger (2010) also estimated divergence times. His results suggest that the spoonbill clade originated about 15 million years ago (with large error bars). That time span is more than sufficient to evolve even such a distinctive bill. The Hawaiian Honeycreepers evolved theirs in half that time (Lerner et al, 2011).

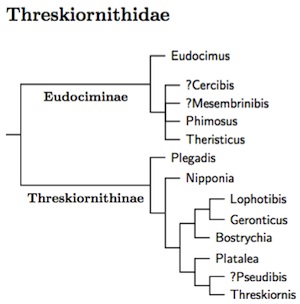

Krattinger did find a deep division in Threskiornithidae, but it was between the exclusively New World genera (Eudociminae) and the rest (Threskiornithinae), not between the ibises and spoonbills. The treatment as subfamilies emphasizes this radical change in taxonomy of the ibises and spoonbills.

Krattinger (2010) examined DNA from just over half of Threskiornithidae. The exact position of some of the Old World genera was not conclusively resolved (Bostrychia, Lophotibis, Nipponia), but this tree is a reasonable interpretation of what Krattinger found. The resulting tree is also consistent with Chesser et al. (2010) and Sibley and Ahlquist (1990). Question marks indicate genera that were not sampled. The order within the spoonbills is based on Chesser et al. (2010), which included all of the spoonbills.

Current thinking is that the extinct Reunion Solitaire was actually an ibis! Moreover, it seems to have been closely related to the sacred-ibises (see Mourer-Chauviré et al., 1995). Accordingly, it appears at the head of Threskiornis.

You may think it odd that the family is called Threskiornithidae when Eudociminae is a much older name. The family was once referred to as Ibididae (based on Ibis Cuvier 1816), but the oldest use of the genus Ibis actually refers to the Mycteria storks. Ibididae had to be replaced, and everyone ultimately settled on basing it on Threskiornis, which replaced Cuvier's version of Ibis. Ultimately, the ICZN ruled on this (Opinion 1674) and the family is called Threskiornithidae.

Eudociminae Bonaparte, 1854

Threskiornithinae Poche, 1904

PELECANIFORMES Sharpe 1891

The status of two monotypic families, the Shoebill and the Hamerkop, has been a perennial issue. The analyses of Ericson et al. (2006a) and Hackett et al. (2008) indicate that both are relatives of the pelicans. Indeed, they could all be lumped into the same family. We keep them separate not only because of their uniqueness, but also because the division between them seems to be ancient. Gibb et al. (2013) estimate that the pelican-shoebill split occurred in the early Eocene. According to Prum et al., the Shoebill is more closely related to the Pelicans and the Hamerkop is basal in the Pelicaniformes.

Scopidae: Hamerkop Bonaparte, 1849

1 genus, 1 species HBW-1

Balaenicipitidae: Shoebill Bonaparte, 1853

1 genus, 1 species HBW-1

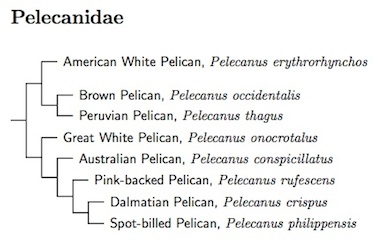

Pelecanidae: Pelicans Rafinesque 1815

|

| Pelican species tree |

|---|

The pelicans have been studied by Kennedy et al. (2013). The arrangement on the tree and order below reflects the relationships they found. Note how the New World Pelicans and Old World Pelicans form sister clades. They also found that the Pink-backed, Dalmatian, and Spot-billed Pelicans are quite closely related.

1 genus, 8 species HBW-1

ARDEIFORMES Wagler, 1830

Ardeidae: Herons, Egrets, Bitterns Leach, 1820

20 genera, 72 species HBW-1

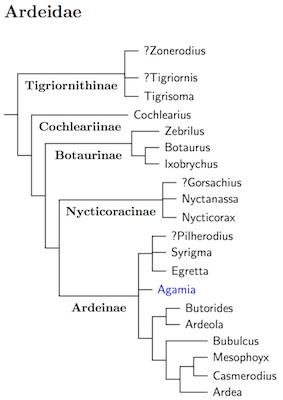

The Boat-billed Heron was previously considered to be the only member of

the Cochlearidae, but is now just another heron. The list here is pieced

together from the limited DNA evidence available (Chang et al., 2003;

Sheldon et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2014) and more traditional

morphological evidence (McCracken and Sheldon, 1998).

The Boat-billed Heron was previously considered to be the only member of

the Cochlearidae, but is now just another heron. The list here is pieced

together from the limited DNA evidence available (Chang et al., 2003;

Sheldon et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2014) and more traditional

morphological evidence (McCracken and Sheldon, 1998).

The DNA evidence puts the Tigriornithinae (tiger-herons) first, followed by the Cochlearinae (Boat-billed Heron). Next are the Botaurinae (bitterns) including Zebrilus, Botaurus and Ixobrychus. Chang et al. (2003), Päckert et al. (2014), and Zhou et al. (2014) found the Black Bittern embedded in Ixobrychus. It's sometimes put in a monotypic genus Dupetor, which is here considered part of Ixobrychus.

All but three of the Botaurinae were considered by Päckert et al. (2014). The linear order here is based on their results, except that they found the Least Bittern, Ixobrychus exilis, closer to Botaurus than to the other Ixobrychus. They looked at the barcoding region and part of cytochrome-b. The barcoding results were a bit strange. The cyt-b + barcoding phylogeny was much more reasonable, but I'm not convinced about moving the Least Bittern to Botaurus. That said, even though they look similar, it's not surprising that the Least Bittern is not sister to the Little Bittern group (I. minutus–novaezelandiae). The osteological evidence in McCracken and Sheldon (1998) had long ago indicated it is not as close to the Little Bittern group as one might think.

It's not at all clear what happens with the night-herons. There's some evidence that they are a clade, but that is incomplete and has only weak genetic support. Some analyses come to different conclusions. Zhou et al. (2014) had Nycticorax grouped with Egretta, but suggested it might be an artifact of long-branch attraction. For the present, I still treat them as a subfamily, Nycticoracinae.

The remaining genera seem to be more closely related to each other than to anything else, and are placed in subfamily Ardeinae. They mostly fall into two main clades. I've put Agamia between the two clades, but the blue coloration indicates this lacks any real evidence.

We consider the Ardea clade first. The Great Egret is sometimes put in a separate genus, Casmerodius. The 12S rRNA tree of Chang et al. puts them sister to the Intermediate Egret, and both sister to Ardea. Sheldon et al. (2000) didn't include the Intermediate Egret, but also found Casmerodius sister to Ardea. This is also why the Intermediate Egret is placed in Mesophoyx. Note that both of these are sometimes put in Egretta, but the DNA says no on this. The placement of Bubulcus follows Chang et al., (2003) Sheldon et al. (2000), and Zhou et al. (2014). The last is based on the complete mitochondrial genome. Zhou et al. actually suggest merging Bubulcus, Casmerodius, Mesophoyx, into Ardea. However, these are both distinctive and genetically distant from the main Ardea group and better maintained as separate genera. Zhou et al. also found that Butorides is sister to Ardeola and that they are basal in the Ardea clade.

Kushlan and Hancock (2005) and Christidis and Boles (2008) suggested treating the Great Egret as two species: Casmerodius albus and Casmerodius modestus. Certainly, the genetic distance between some of the Great Egret subspecies is quite large, comparable to that between Great and Intermediate Egret (Sheldon, 1987), but the subspecies analyzed are egretta and modestus. This suggest no significant gene flow between egretta and modestus, that they are distinct biological species. But how do the other subspecies (albus and melanorhynchos) fit in? Both Kushlan and Hancock, and Cristidis and Boles, suggest that egretta should be grouped with albus and melanorhynchos. However, Pratt (2011) argues that the split should be between egretta and the rest, mainly on the basis of breeding plumage. The evidence is just not there to draw a definitive conclusion. However, it seems clear enough that the Great Egret actually includes two or more species. I think this needs to be acknowledged, and that Pratt's arrangement makes more sense. In other words, the Great Egret has been split into the monotypic American Egret, Casmerodius egretta, and Great Egret, Casmerodius albus (including melanorhynchos and modestus).

The other group is the Egretta clade. Syrigma seems to belong here according to the DNA. That makes it natural to include Pilherodius too, but the relationships between all of these are unclear.

Besides the Great Egret complex, there are at least two taxa which have subspecies that might be promoted to full species status, the Cattle Egret (split by IOC) and the Striated Heron.

The status of the Great White Heron, Ardea herodias occidentalis, remains controversial (e.g., Stevenson and Anderson, 1994). It is very near the borderline for species status. Genetically, it is nested within the larger Great Blue Heron clade. However, in their overlap zone in extreme south Florida, there seems to be little interbreeding between the dimorphic Great White Herons (the dark morph is sometimes called Würdemann's Heron) and the monomorphic Great Blue Herons (McGuire, 2002). Moreover, the Great Blue Herons of the Florida peninsula (wardii) are more closely related to those of the northern US (herodias) than to occidentalis. However wardii and herodias are closer to occidentalis than any of them are to fannini. For the present, I'm following AOU by treating them as one species although I'm not convinced this is correct.